Many of us hacker types with some hardware knowledge and a smattering of embedded experience would like to get into home automation, but there can be quite a learning curve. If you’re looking for a hackable starting point; something to deploy, learn about and then later expand upon, then look no further than the PicoW Home Assistant Starter project from [Danilo Campos].

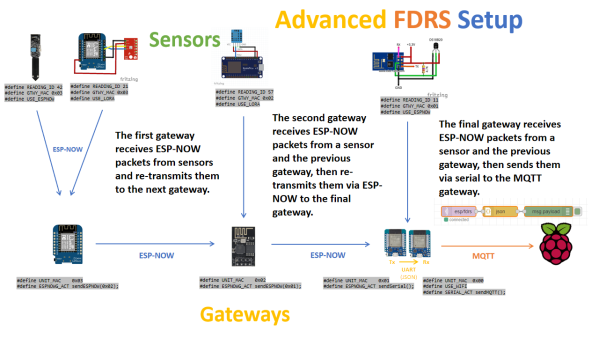

The project is based upon the arduino-pico core, which supports a whole pile of RP2040-based boards, so you don’t need to restrict yourself to the “official” Pico-W, so long as you have working networking, Wi-Fi or otherwise. Integration is provided by the arduino-home-assistant library, which acts as the bridge between your sensors and other widgets, MQTT, and thence the network beyond. Events and sensor data on the end-point are packaged up with MQTT and published out to the broker via the network provided, all for minimal initial effort. Once you’ve got the basic connectivity to your Home Assistant instance working, there are many code examples in the arduino-home-assistant GitHub page to give you a helping start to connect whatever tickles your fancy.

It turns out we’ve covered HA quite a bit on these fair pages, like for example, these sweet automated window blinds. Another hack uses load cells under the bed legs to detect if someone is in bed or not, and if this isn’t your thing, maybe your idea of a home assistant is a bit more like this one?