The future we know today looks very different than the one envisioned in the 60s and 70s. For starters, it has far too few Nixie tubes. An oversight [nixiebunny] wants to address with his Nixie tube instrument panel.

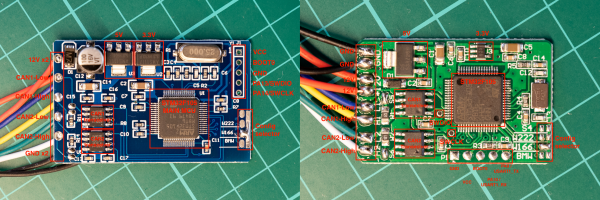

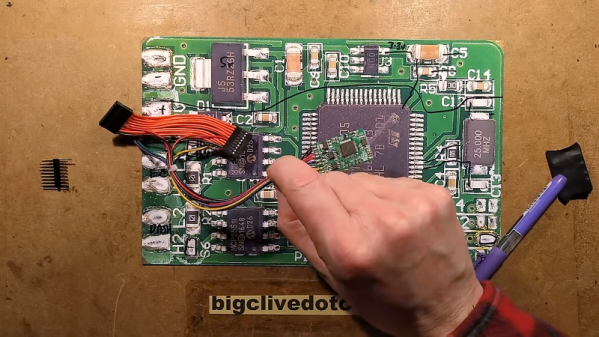

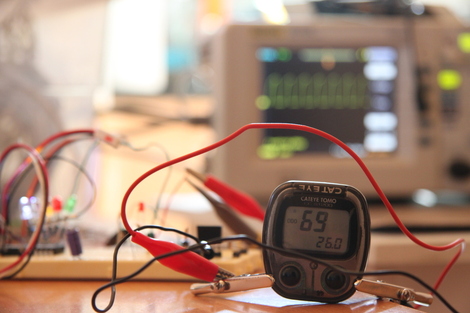

All the essential info is there: engine temperature, tachometer, speed, battery voltage, and even odometer. You might have noticed that there isn’t a clock. The justification that [nixiebunny] gives is that he’s always wearing his Nixie watch, so a clock in his car seems redundant. There is also a gap in the panel to allow an oil pressure display. Corvairs are known for throwing belts next to the oil sender, so any attached sensor needs to be designed well and thought through. A Teensy receives engine telemetry data (no OBDII port to hook into — GM didn’t come out with the first OBD port until the 80s) from the engine bay. The data is transformed into SPI data sent to the 74HC595 shift register chain via a CAT5 cable. Details are a little sparse, but we can see a custom PCB to fit the shape of the hole in the dash with the different Nixie tube footprints silkscreened on.

We love seeing Nixie tubes in unexpected places. Like this POV Nixie clock or this Nixie robot sculpture.