When it comes to knowledge there are things you know as facts because you have experienced them yourself or had them verified by a reputable source, and there are things that you know because they are common knowledge but unverified. The former are facts, such as that a 100mm cube of water contains a litre of the stuff, while the latter are received opinions, such as the belief among Americans that British people have poor dental care. The first is a verifiable fact, while the second is subjective.

In our line there are similar received opinions, and one of them is that you shouldn’t print with old 3D printing filament because it will ruin the quality of your print. This is one I can now verify for myself, because I was recently given a part roll of blue PLA from a hackerspace, that’s over a decade old. It’s not been stored in a special environment, instead it’s survived a run of dodgy hackerspace premises with all the heat and humidity that’s normal in a slightly damp country. How will it print?

It Ain’t Stringy

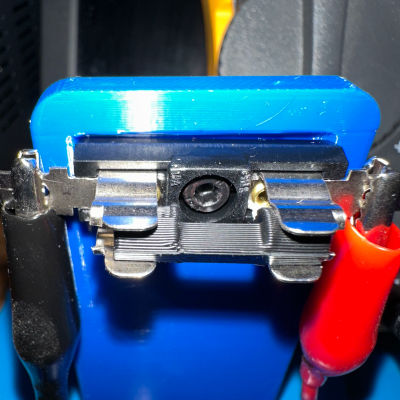

In the first instance, looking at the filament, it looks like any other filament. No fading of the colour, no cracking, if I didn’t know its age it could have been opened within the last few weeks. It loads into the printer, a Prusa Mini, fine, it’s not brittle, and I’m ready to print a Benchy.