For [Peter Jansen], the most interesting course in grad school was Advanced Brain Imaging; each class was a lecture followed by a trip to the imaging lab where grad students would take turns being holed up in a MRI machine. A few years into his doctorate, [Peter] found himself in a very opportune situation – his local hackerspace just acquired a shiny new laser cutter, he had some free time on his hands, and the dream of creating a medical imaging device was still in the back of his mind. A few weeks later, the beginnings of an open source CT scanner began to take shape.

This isn’t an MRI machine that [Peter] so fondly remembered from grad school. A good thing, that, as superconducting magnets chilled with liquid helium is a little excessive for a desktop unit. Instead, [Peter] is building a CT scanner, a device that takes multiple x-ray ‘slices’ around an axis of rotation. These slices can then be recompiled into a 3D visualization of the inside of any object.

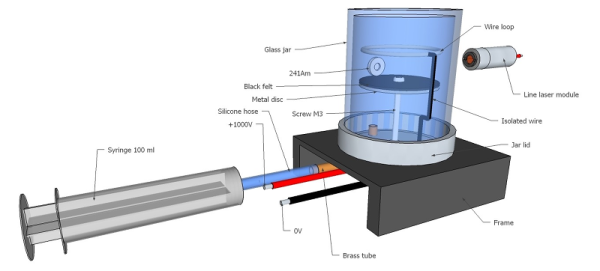

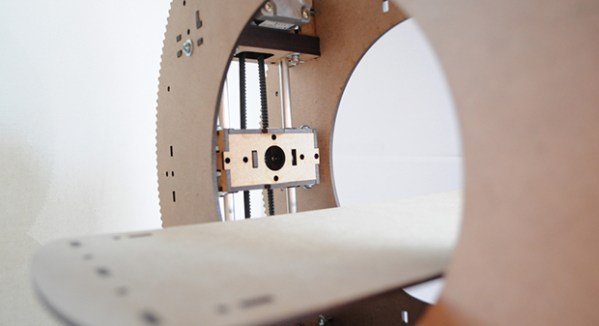

The mechanics of the build are a Stargate-like torus with stepper motor moving back and forth inside the disk. This, combined with the rotation of the disk and moving the bed back and forth allow the imager to position itself anywhere along an object.

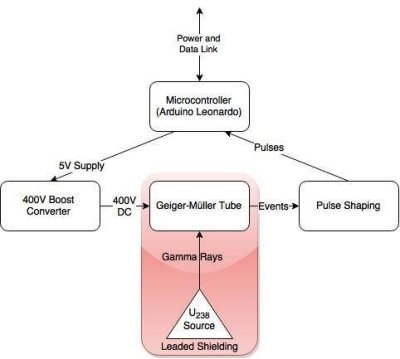

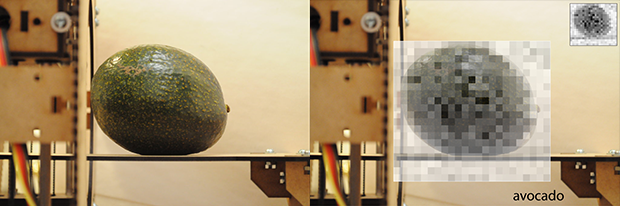

For the radioactive detector, [Peter] is using a CCD marketed as a high-energy particle detector by Radiation Watch. Not only does this allow for an easy interface with a microcontroller, it’s also much smaller than big, heavy photomultiplier tubes found in old CT scanners. As for the source, [Peter] is going for very low intensity sources, most likely Barium or Cadmium that will take many minutes to capture a single slice.

The machine operates just above normal background radiation, so while being extremely safe for a desktop CT scanner, it is, however, very slow. This doesn’t bother [Peter], as ‘free’ time on a CT scanner allows for some very interesting, not seen before visualizations, such as a plant growing from a seed, spreading its roots, and breaking the surface as a seedling.

[Peter] still has some work to do on his desktop CT scanner, but once the stepper motor and sensor board are complete, he should be well on his way towards scanning carrots, apples, and just about everything else around his house.