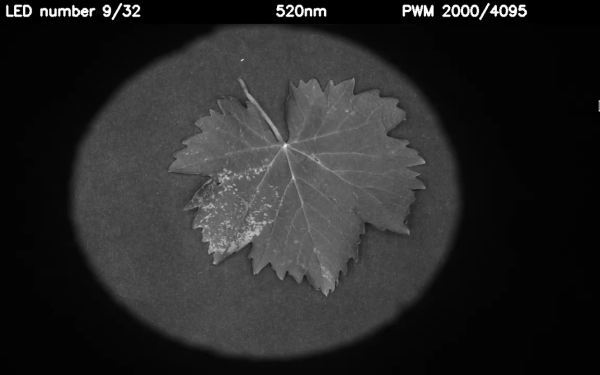

Multispectral imaging can be a useful tool, revealing all manner of secrets hidden to the human eye. [elad orbach] built a rig to perform such imaging using the humble Raspberry Pi.

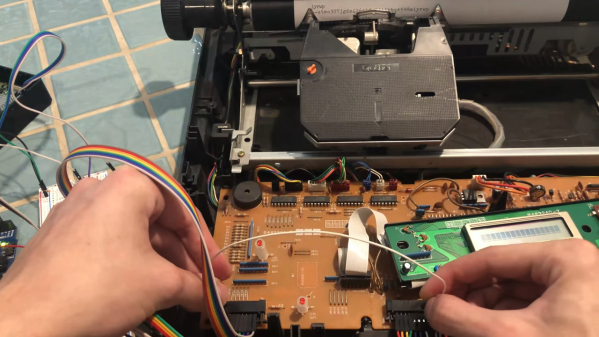

The project is built inside a dark box which keeps outside light from polluting the results. A camera is mounted at the top to image specimens installed below, which the Pi uses to take photos under various lighting conditions. The build relies on a wide variety of colored LEDs for clean, accurate light output for accurate imaging purposes. The LEDs are all installed on a large aluminium heatsink, and can be turned on and off via the Raspberry Pi to capture images with various different illumination settings. A sheath is placed around the camera to ensure only light reflected from the specimen reaches the camera, cutting out bleed from the LEDs themselves.

Multispectral imaging is particularly useful when imaging botanical material. Taking photos under different lights can reveal diseases, nutrient deficiencies, and other abnormalities affecting plants. We’ve even seen it used to investigate paintings, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Multispectral Imaging System Built With Raspberry Pi”