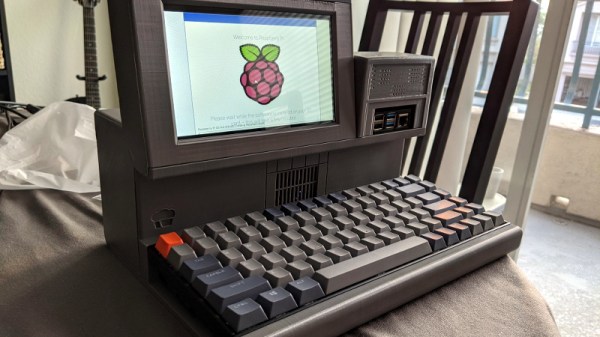

What makes a cyberdeck? Looking as though it came from an alternate reality version of the 1980s is a good start, but certainly isn’t required. If you’re really trying to adhere to the cyberpunk ethos, any good deck should be modular enough that it can be easily repaired and upgraded over time. In fact, if it’s not in a constant state of evolution and flux, you’ve probably done something wrong. If you can hit those goals and make it look retro-futuristic at the same time, even better.

Which is why the Clockwork DevTerm is such an interesting device. It ticks off nearly every box that the custom cyberdeck builds we’ve covered over the last couple years have, while at the same time being approachable enough for a more mainstream audience. You won’t need a 3D printer, soldering iron, or hot glue gun to build your own DevTerm. Of course if you do have those tools and the skills to put them to work, then this might be the ideal platform to build on.

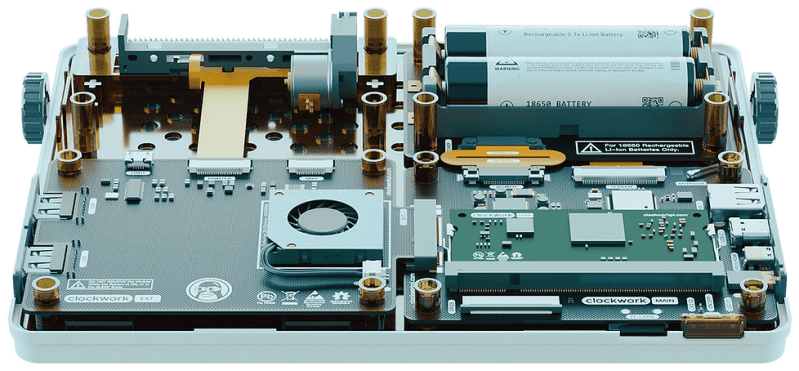

With a 65% QWERTY keyboard and widescreen display, the DevTerm looks a lot like early portable computers such as the TRS-80 Model 100. But unlike the machines it draws inspiration from, the display is a 6.8 inch 1280 x 480 IPS panel, and there’s no pokey Intel 8085 chip inside. The $220 USD base model is powered by the Raspberry Pi Compute Module 3, and if you need a little more punch, there are a few higher priced options that slot in a more powerful custom module. Like the Waveshare Pi CM laptop we recently looked at, there’s sadly no support for the newer CM4; but at least the DevTerm is modular enough that it doesn’t seem out of the question that Clockwork could release a new mainboard down the line. Or perhaps somebody in the community will even do it for them.

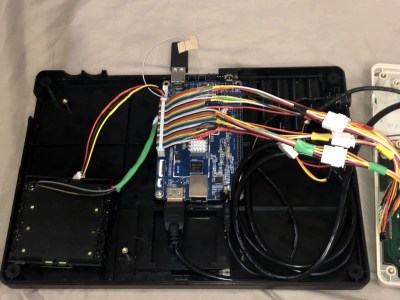

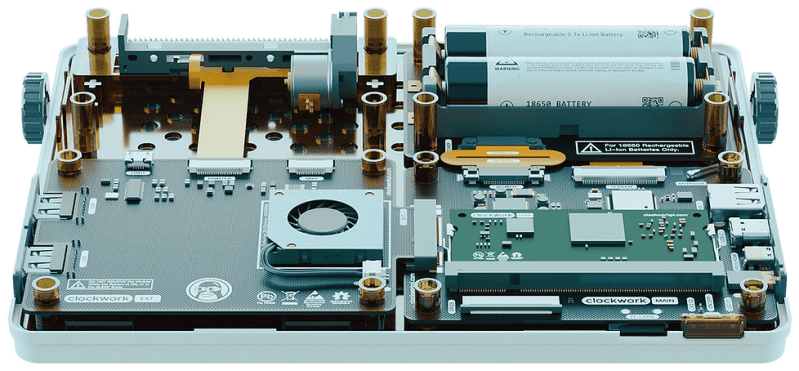

Speaking of which, the board in the DevTerm has been designed in two pieces so that “EXT Module” side can be swapped out with custom hardware without compromising the core functionality of the system. The stock board comes with extra USB ports, a micro USB UART port for debugging, a CSI camera connector, and an interface for an included thermal printer that slots into a bay on the rear of the computer. Clockwork says they hope the community really runs wild with their own EXT boards, especially since the schematics and relevant design files for the entire system are all going to be put on GitHub and released under the GPL v3.

They say that anything that sounds too good to be true probably is, and if we’re honest, we’re getting a little of that from the DevTerm. An (CPU BLOBs aside!) open hardware portable Linux computer with this kind of modularity is basically a hacker’s dream come true, and thus far the only way to get one was to build it yourself. It’s hard to believe that Clockwork will be able to put something like this out for less than the cost of a cheap laptop without cutting some serious corners somewhere, but we’d absolutely love to be proven wrong when it’s released next year.