Folks who like the take the old Amiga out for the occasional Sunday drive usually do it because they have wistful memories of the simpler times. Back when you could edit documents or view spreadsheets on a machine that had RAM measured in kilobytes instead of gigabytes. But even the most ardent retro computer aficionado usually allows for a bit of modern convenience.

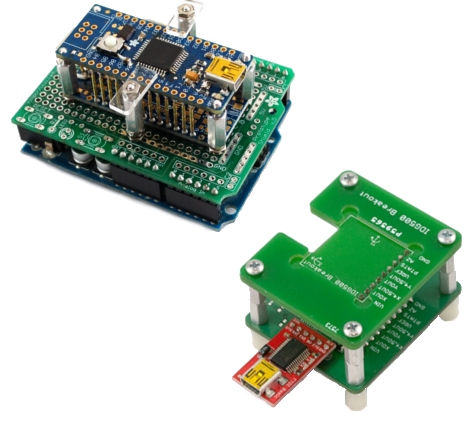

Enter the mouSTer. This tiny device converts a common USB HID mouse into something older computers can understand. It even supports using Sony’s PlayStation 4 controller as a generic game pad. While the firmware is still getting tweaked, the team has confirmed its working on several classic machines and believe it should work on many more. Considering the prices that some of these old peripherals command on the second hand market, using a USB mouse or controller on your vintage computer isn’t just more convenient, but will likely be a lot cheaper.

Confirmed retrocomputing superfan [Drygol] is a member of the team working on mouSTer, and in a recent post to his retrohax blog, he talks a bit about what’s happened since his last update over the summer. He also talks a bit about the challenges they’ve faced to get it into production. Even if you’re not into poking around on vintage computers, there are lessons to be learned here about what it takes to move from a handful of prototypes to something you can actually sell to the public.

Confirmed retrocomputing superfan [Drygol] is a member of the team working on mouSTer, and in a recent post to his retrohax blog, he talks a bit about what’s happened since his last update over the summer. He also talks a bit about the challenges they’ve faced to get it into production. Even if you’re not into poking around on vintage computers, there are lessons to be learned here about what it takes to move from a handful of prototypes to something you can actually sell to the public.

We especially liked the details about the mouSTer enclosure, or lack thereof. Originally [Drygol] says they were going to have the cases injection molded, but despite initial interest from a few companies they talked to, nobody ended up biting because it needed to be done with relatively uncommon low pressure injection. While 3D printing is still an option, the team ended up using clear heatshrink tubing to create a simple conformal protective shell over the electronics. Personally we think it looks great like this, but it sounds like this is only a temporary solution until something a bit more robust can be implemented.

As you might imagine we’ve seen DIY projects that aimed to bring modern input devices to vintage computers like the Atari ST, but the diminutive proportions of the mouSTer and the fact that it’s a turn-key product is sure to appeal to those who want to minimize headaches when working with their classic gear.