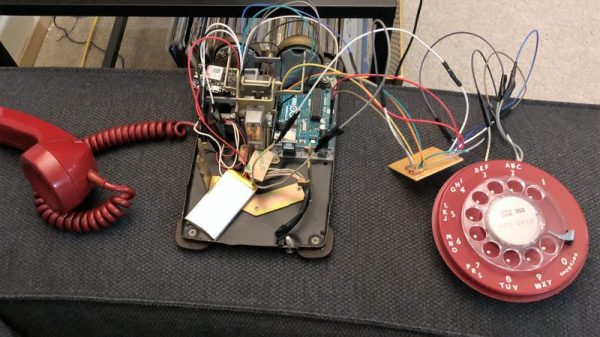

For sturdy utilitarianism, there were few designs better than the Western Electric Model 500 desk phone. The 500 did one thing and did it well, and remained essentially unchanged from the mid-1940s until Touch Tone phones started appearing in the early 70s. That doesn’t mean it can’t have a place in the modern phone system, though, as long as you’re willing to convert it into a cellphone.

Luckily for [bicapitate], the Model 500 has plenty of room inside the case once the network interface is removed, because the new electronics take up a fair bit of space. There’s no build log per se, but the photo album makes it clear what’s going on. An Arduino reads the hook switch and dial pulses, while a Fona GSM module takes care of the cellular side of things. It looks like a small electret mic and a speaker replace the original transmitter and receiver. As a nice touch, the original ringer is used, but instead of trying to drive it electrically, [bicapitate] came up with a simple cam mechanism on a small motor. Driven at the right speed, the cam hooks the clapper arm, rings one bell, then releases it to let the clapper spring back to hit the other bell. Everything is powered by a LiPo, so it could be taken to the local coffee shop for some hipster hijinks.

We’ve seen similar retro-mods like this before using phones from all over the world; here’s a British take and one from Belgium, both using phones with equally classic lines.

[via r/arduino]

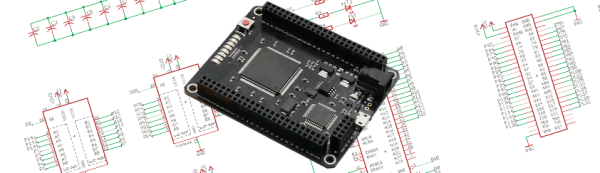

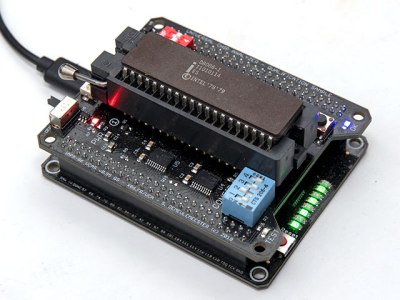

So, how does it actually test? Synthesized inside the FPGA is everything the CPU needs from the motherboard to make it tick, including ROM, RAM, bus controllers, clock generation and interrupt handling. Many testing frequencies are supported (which is helpful for spotting fakes), and if connected to a computer via USB, the UCA can check power consumption, and even benchmark the chip. We can’t begin to detail the amount of thought that’s gone into the design here, from auto-detecting data bus width to the sheer amount of models supported, but you can read more technical details

So, how does it actually test? Synthesized inside the FPGA is everything the CPU needs from the motherboard to make it tick, including ROM, RAM, bus controllers, clock generation and interrupt handling. Many testing frequencies are supported (which is helpful for spotting fakes), and if connected to a computer via USB, the UCA can check power consumption, and even benchmark the chip. We can’t begin to detail the amount of thought that’s gone into the design here, from auto-detecting data bus width to the sheer amount of models supported, but you can read more technical details