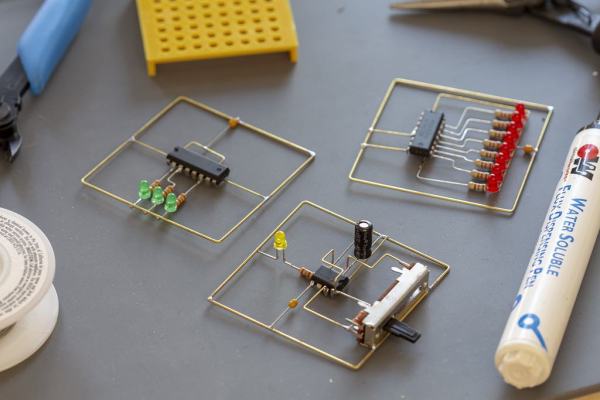

The technique of assembling circuits without substrate goes by many names; you may know it as flywiring, deadbugging, point to point wiring, or freeform circuits. Sometimes this technique is used for practical purposes like fixing design errors post-production or escaping tiny BGA components (ok, that one might be more cool than practical). Perhaps our favorite use is to create art, and [Mohit Bhoite] is an absolute genius of the form. He’s so prolific that it’s difficult to point to a particular one of his projects as an exemplar, though he has a dusty blog we might recommend digging through [Mohit]’s Twitter feed and marveling at the intricate works of LEDs and precision-bent brass he produces with impressive regularity.

tiny BGA components (ok, that one might be more cool than practical). Perhaps our favorite use is to create art, and [Mohit Bhoite] is an absolute genius of the form. He’s so prolific that it’s difficult to point to a particular one of his projects as an exemplar, though he has a dusty blog we might recommend digging through [Mohit]’s Twitter feed and marveling at the intricate works of LEDs and precision-bent brass he produces with impressive regularity.

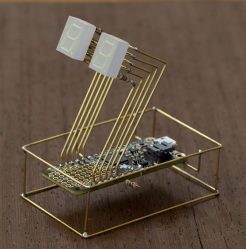

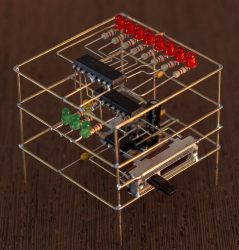

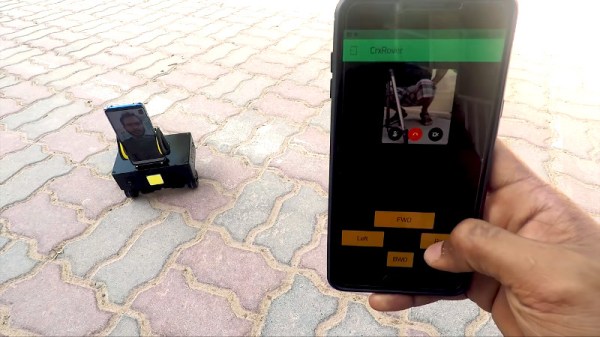

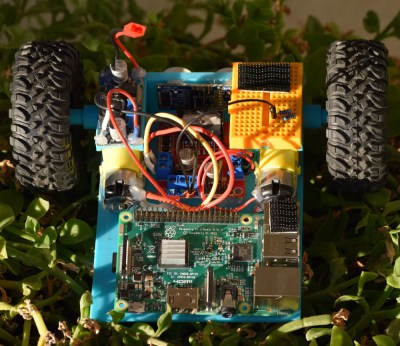

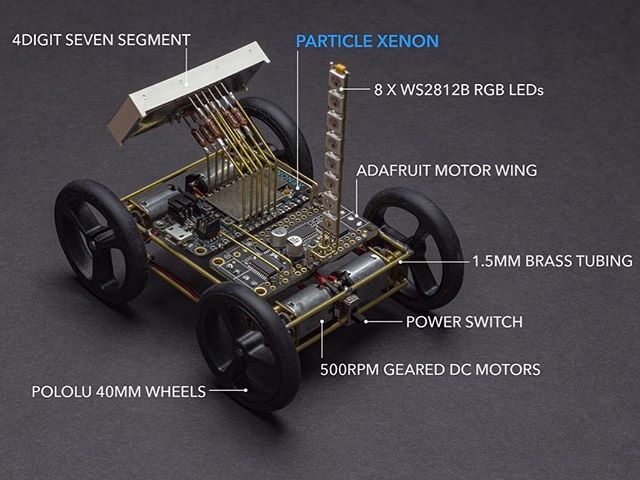

So where to begin? Very recently [Mohit] put together a small wheeled vehicle for persistence of vision drawing (see photo above). We’re pretty excited to see some more photos and videos he takes as this adorable little guy gets some use! Going a little farther back in time there’s this microcontroller-free LED scroller cube which does a great job showing off his usual level of fit and finish (detail here). If you prefer more LEDs there’s also this hexagonal display he whipped up. Or another little creature with seven segment displays for eyes. Got those? That covers (most) of his last month of work. You may be starting to get a sense of the quality and quantity on offer here.

We’ve covered other examples of similar flywired circuits before. Here’s one of [Mohit]’s from a few years ago. And another on an exquisite headphone amp encased in a block of resin. What about a high voltage Nixie clock that’s all exposed? And check out a video of the little persistence of vision ‘bot after the break.

Thanks [Robot] for reminding us that we hadn’t paid enough attention to [Mohit]’s wonderful work!