[DTSS_Smudge] correctly intuits that if you are interested in an old Heathkit signal generator, you probably already know how to solder. So, in a recent video, he focused on the components he decided to update for safety and other reasons. Meanwhile, we get treated to a nice teardown of this iconic piece of test gear.

If you didn’t grow up in the 1960s, it seems strange that the device has a polarized line cord with one end connected to the chassis. But that used to be quite common, just like kids didn’t wear helmets on bikes in those days.

A lot of TVs were “hot chassis” back then, too. We were always taught to touch the chassis with the back of your hand first. That way, if you get a shock, the associated muscle contraction will pull your hand away from the electricity. Touching it normally will make you grip the offending chassis hard, and you probably won’t be able to let go until someone kindly pulls the plug or a fuse blows.

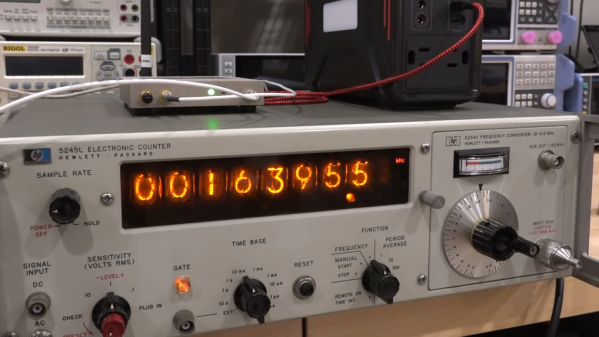

These signal generators were very common back in the day. A lot of Heathkit gear was very serviceable and more affordable than the commercial alternatives. In 1970, these cost about $32 as a kit or $60 already built. While $32 doesn’t sound like much, it is equivalent to $260 today, so not an impulse buy.

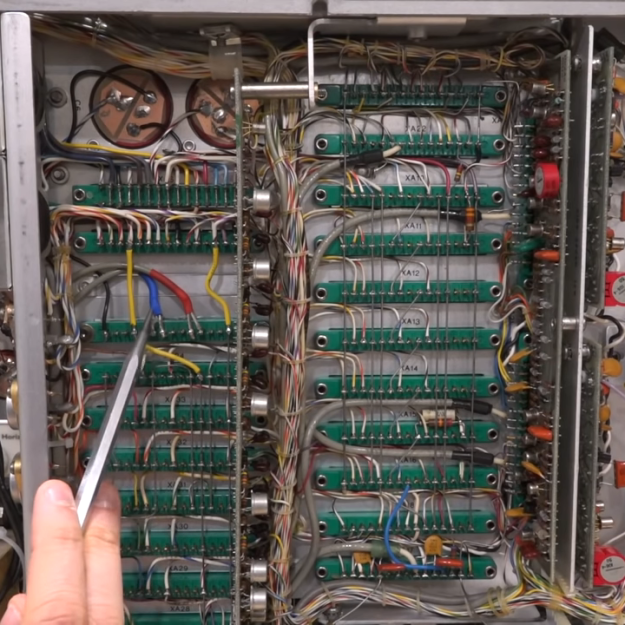

Some of the parts are simply irreplaceable. The variable capacitor would be tough to source since it is a special type. The coils would also be tough to find replacements, although you might have luck rewinding them if it were necessary.

We are spoiled today with so many cheap quality instruments available. However, there was something satisfying about building your own gear and it certainly helped if you ever had to fix it.

There was so much Heathkit gear around that even though they’ve been gone for years, you still see quite a few units in use. Not all of their gear had tubes, but some of our favorite ones did.

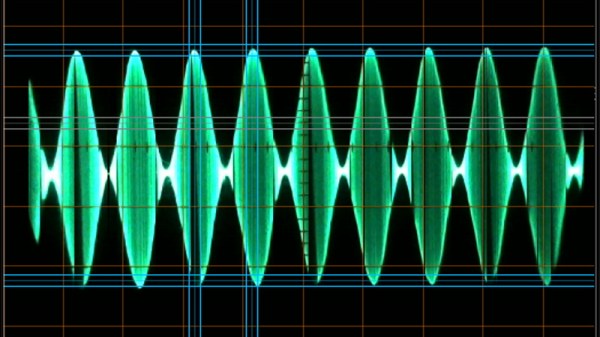

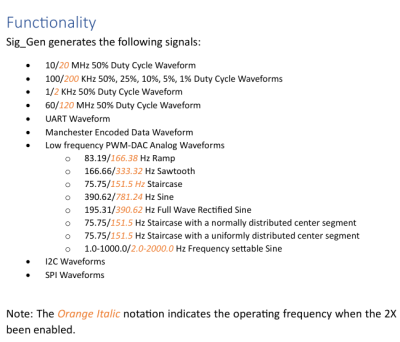

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.