Why is it always a helium leak? It seems whenever there’s a scrubbed launch or a narrowly averted disaster, space exploration just can’t get past the problems of helium plumbing. We’ve had a bunch of helium problems lately, most famously with the leaks in Starliner’s thruster system that have prevented astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams from returning to Earth in the spacecraft, leaving them on an extended mission to the ISS. Ironically, the launch itself was troubled by a helium leak before the rocket ever left the ground. More recently, the Polaris Dawn mission, which is supposed to feature the first spacewalk by a private crew, was scrubbed by SpaceX due to a helium leak on the launch tower. And to round out the helium woes, we now have news that the Peregrine mission, which was supposed to carry the first commercial lander to the lunar surface but instead ended up burning up in the atmosphere and crashing into the Pacific, failed due to — you guessed it — a helium leak.

Continue reading “Hackaday Links: September 1, 2024”

SpaceX103 Articles

Model Rocket Nails Vertical Landing After Three-Year Effort

Model rocketry has always taken cues from what’s happening in the world of full-scale rockets, with amateur rocketeers doing their best to incorporate the technologies and methods into their creations. That’s not always an easy proposition, though, as this three-year effort to nail a SpaceX-style vertical landing aptly shows.

First of all, hats off to high schooler [Aryan Kapoor] from JRD Propulsion for his tenacity with this project. He started in 2021 with none of the basic skills needed to pull off something like this, but it seems like he quickly learned the ropes. His development program was comprehensive, with static test vehicles, a low-altitude hopper, and extensive testing of the key technology: thrust-vector control. His rocket uses two solid-propellant motors stacked on top of each other, one for ascent and one for descent and landing. They both live in a 3D printed gimbal mount with two servos that give the stack plus and minus seven degrees of thrust vectoring in two dimensions, which is controlled by a custom flight computer with a barometric altimeter and an inertial measurement unit. The landing gear is also clever, using rubber bands to absorb landing forces and syringes as dampers.

The video below shows the first successful test flight and landing. Being a low-altitude flight, everything happens very quickly, which probably made programming a challenge. It looked like the landing engine wasn’t going to fire as the rocket came down significantly off-plumb, but when it finally did light up the rocket straightened and nailed the landing. [Aryan] explains the major bump after the first touchdown as caused by the ascent engine failing to eject; the landing gear and the flight controller handled the extra landing mass with aplomb.

All in all, very nice work from [Aryan], and we’re keen to see this one progress.

Continue reading “Model Rocket Nails Vertical Landing After Three-Year Effort”

Hackaday Links: July 7, 2024

Begun, the Spectrum Wars have. First, it was AM radio getting the shaft (last item) and being yanked out of cars for the supposed impossibility of peaceful coexistence with rolling broadband EMI generators EVs. That battle has gone back and forth for the last year or two here in the US, with lawmakers even getting involved at one point (first item) by threatening legislation to make terrestrial AM radio available in every car sold. We’re honestly not sure where it stands now in the US, but now the Swiss seem to be entering the fray a little up the dial by turning off all their analog FM broadcasts at the end of the year. This doesn’t seem to be related to interference — after all, no static at all — but more from the standpoint of reclaiming spectrum that’s no longer turning a profit. There are apparently very few analog FM receivers in use in Switzerland anymore, with everyone having switched to DAB+ or streaming to get their music fix, and keeping FM transmitters on the air isn’t cheap, so the numbers are just stacked against the analog stations. It’s hard to say if this is a portent of things to come in other parts of the world, but it certainly doesn’t bode well for the overall health of terrestrial broadcasting. “First they came for AM radio, and I did nothing because I’m not old enough to listen to AM radio. But then they came for analog FM radio, and when I lost my album-oriented classic rock station, I realized that I’m actually old enough for AM.”

NASA Adjusts Course On Journey To The Moon

It’s already been more than fifty years since a human last stepped foot on another celestial body, and now that NASA has officially pushed back key elements of their Artemis program, we’re going to be waiting a bit longer before it happens again. What’s a few years compared to half a century?

The January 9th press conference was billed as a way for NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and other high-ranking officials within the space agency to give the public an update on Artemis. But those who’ve been following the program had already guessed it would end up being the official concession that NASA simply wasn’t ready to send astronauts out for a lunar flyby this year as initially planned. Pushing back this second phase of the Artemis program naturally means delaying the subsequent missions as well, though during the conference it was noted that the Artemis III mission was already dealing with its own technical challenges.

The January 9th press conference was billed as a way for NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and other high-ranking officials within the space agency to give the public an update on Artemis. But those who’ve been following the program had already guessed it would end up being the official concession that NASA simply wasn’t ready to send astronauts out for a lunar flyby this year as initially planned. Pushing back this second phase of the Artemis program naturally means delaying the subsequent missions as well, though during the conference it was noted that the Artemis III mission was already dealing with its own technical challenges.

More than just an acknowledgement of the Artemis delays, the press conference did include details on the specific issues that were holding up the program. In addition several team members were able to share information about the systems and components they’re responsible for, including insight into the hardware that’s already complete and what still needs more development time. Finally, the public was given an update on what NASA’s plans look like after landing on the Moon during the Artemis III mission, including their plans for constructing and utilizing the Lunar Gateway station.

With the understanding that even these latest plans are subject to potential changes or delays over the coming years, let’s take a look at the revised Artemis timeline.

Continue reading “NASA Adjusts Course On Journey To The Moon”

Veteran SpaceX Booster Lost Due To Rough Seas

With the notable exception of the now retired Space Shuttle orbiters, essentially every object humanity ever shot into space has been single-use only. But since December of 2015, SpaceX has been landing and refurbishing their Falcon 9 boosters, with the end goal of operating their rockets more like cargo aircraft. Today, while it might go unnoticed to those who aren’t closely following the space industry, the bulk of the company’s launches are performed with boosters that have already completed multiple flights.

This reuse campaign has been so successful these last few years that the recent announcement the company had lost B1058 (Nitter) came as quite a surprise. The 41 meter (134 foot) tall booster had just completed its 19th flight on December 23rd, and had made what appeared to be a perfect landing on the drone ship Just Read the Instructions. But sometime after the live stream ended, SpaceX says high winds and powerful waves caused the booster to topple over.

Continue reading “Veteran SpaceX Booster Lost Due To Rough Seas”

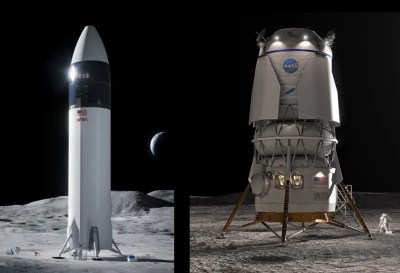

Artemis’ Next Giant Leap: Orbital Refueling

By the end of the decade, NASA’s Artemis program hopes to have placed boots back on the Moon for the first time since 1972. But not for the quick sightseeing jaunts of the Apollo era — the space agency wants to send regular missions made up of international crews down to the lunar surface, where they’ll eventually have permanent living and working facilities.

The goal is to turn the Moon into a scientific outpost, and that requires a payload delivery infrastructure far more capable than the Apollo Lunar Module (LM). NASA asked their commercial partners to design crewed lunar landers that could deliver tens of tons of to the lunar surface, with SpaceX and Blue Origin ultimately being awarded contracts to build and demonstrate their vehicles over the next several years.

At a glance, the two landers would appear to have very little in common. The SpaceX Starship is a sleek, towering rocket that looks like something from a 1950s science fiction film; while the Blue Moon lander utilizes a more conventional design that’s reminiscent of a modernized Apollo LM. The dichotomy is intentional. NASA believes there’s a built-in level of operational redundancy provided by the companies using two very different approaches to solve the same goal. Should one of the landers be delayed or found deficient in some way, the other company’s parallel work would be unaffected.

But despite their differences, both landers do utilize one common technology, and it’s a pretty big one. So big, in fact, that neither lander will be able to touch the Moon until it can be perfected. What’s worse is that, to date, it’s an almost entirely unproven technology that’s never been demonstrated at anywhere near the scale required.

Continue reading “Artemis’ Next Giant Leap: Orbital Refueling”

Hackaday Links: May 21, 2023

The reports of the death of automotive AM radio may have been greatly exaggerated. Regular readers will recall us harping on the issue of automakers planning to exclude AM from the infotainment systems in their latest offerings, which doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense given the reach of AM radio and its importance in public emergencies. US lawmakers apparently agree with that position, having now introduced a bipartisan bill to require AM radios in cars. The “AM for Every Vehicle Act” will direct the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration to draw up regulations requiring every vehicle operating on US highways to be able to receive AM broadcasts without additional fees or subscriptions. That last bit is clever, since it prevents automakers from charging monthly fees as they do for heated seats and other niceties. It’s just a bill now, of course, and stands about as much chance of becoming law as anything else that makes sense does, so we’re not holding our breath on this one. But at least someone recognizes that AM radio still has a valid use case.