The soul of a rock band is its rhythm section, usually consisting of a drummer and bass player. If you don’t believe that, try listening to a band where these two can’t keep proper time. Bands can often get away with sloppy guitars and vocals (this is how punk became a genre), but without that foundation you’ll be hard pressed to score any gigs at all. Unfortunately drums are bulky and expensive, and good drummers hard to find, so if you’re an aspiring bassist looking to practice laying down a solid groove on your own check out this drum machine designed by [Duncan McIntyre].

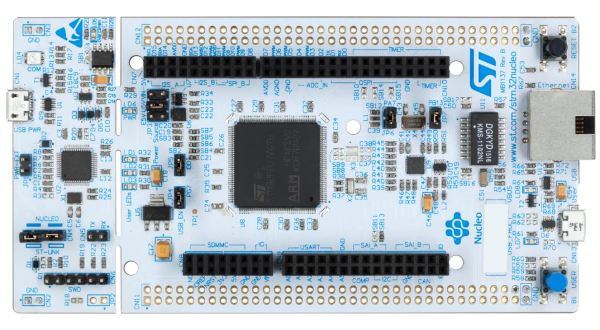

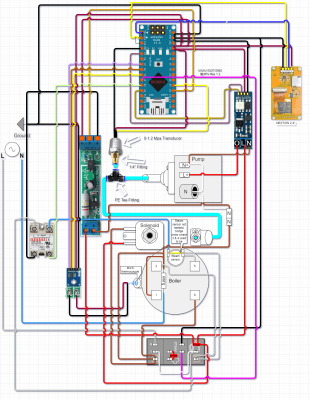

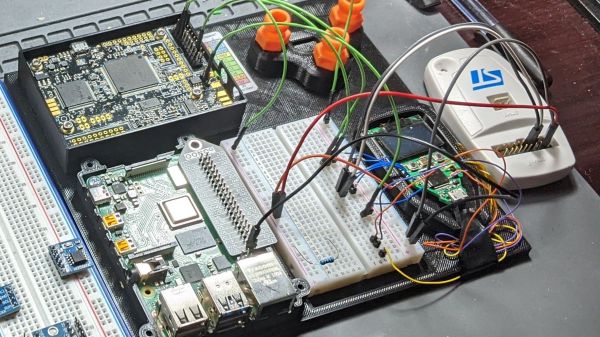

The drum machine is designed to be as user-friendly as possible for someone who is actively playing another instrument, which means all tactile inputs and no touch screens. Several rows of buttons across the top select the drum sounds for the sequencer and each column corresponds to the various beats, allowing custom patterns to be selected and changed rapidly. There are several other controls for volume and tempo, and since it’s based on MIDI using the VS1053 chip and uses an STM32 microcontroller it’s easily configurable and can be quickly interfaced with other machines as well.

For anyone who wants to build their own, all of the circuit schematics and code are available on GitHub. If you have an aversion to digital equipment, though, take a look at this drum machine that produces its rhythms using circuits that are completely analog.