One of the hardest aspects of choosing a career isn’t getting started, it’s keeping up. Whether you’re an engineer, doctor, or even landscaper, there are always new developments to keep up with if you want to stay competitive. This is especially true of farming, where farmers have to keep up with an incredible amount of “best practices” in order to continue being profitable. Keeping up with soil nutrient requirements, changing weather and climate patterns, pests and other diseases, and even equipment maintenance can be a huge hassle.

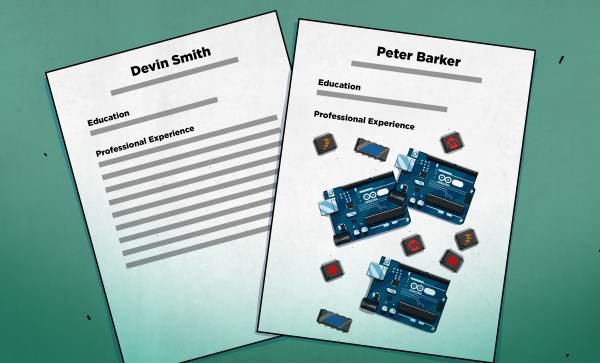

A new project at Hackerfarm led by [Akiba] is hoping to take at least one of those items off of farmers’ busy schedules, though. Their goal is to help farmers better understand the changing technological landscape and make use of technology without having to wade through all the details of every single microcontroller option that’s available, for example. Hackerfarm is actually a small farm themselves, so they have first-hand knowledge when it comes to tending a plot of land, and [Bunnie Huang] recently did a residency at the farm as well.

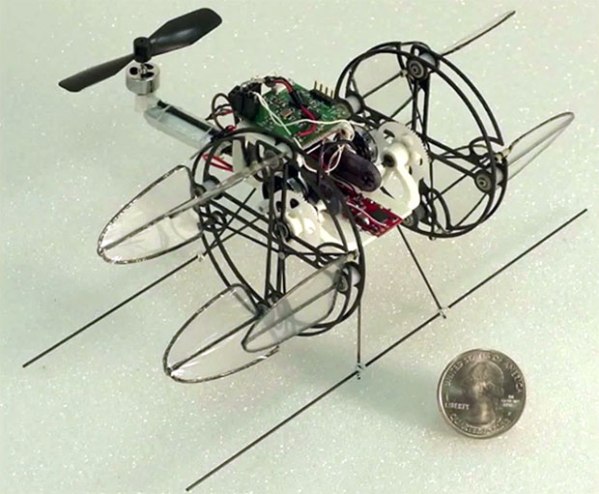

The project strives to be a community for helping farmers make the most out of their land, so if you run a small farm or even have a passing interest in gardening, there may be some useful tools available for you. If you have a big enough farm, you might even want to try out an advanced project like an autonomous tractor.