The Xiaomi LYWSD03MMC temperature and humidity sensor is ridiculously cheap. If you’re buying a few at a time, you can expect to pay as little as $5 USD a pop for these handy Bluetooth Low Energy environmental sensors. Unfortunately, that low price tag comes with a bit of a catch: you can only read the data with the official Xiaomi smartphone application or by linking it to one of the company’s smart home hubs. Or at least, that used to be the case.

Over the past year, [Aaron Christophel] has been working on a replacement firmware for these Xiomi sensors that unlocks the data so you can use it however you see fit. In addition, it allows the user to tweak various features and settings that were previously unavailable. For example, you can disable the little ASCII-art smiley face that usually shows on the LCD to indicate the relative comfort level of the room.

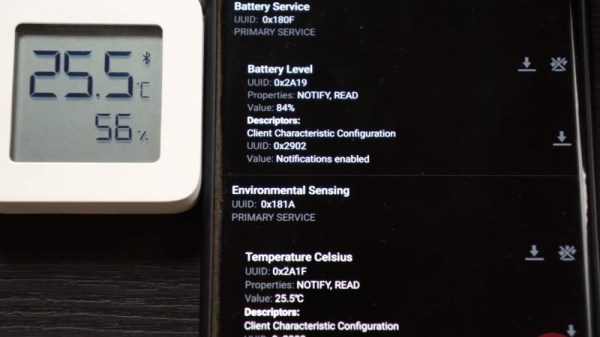

The new firmware publishes the temperature, humidity, and battery level every minute through a BLE advertisement broadcast. In other words, that means client devices can read data from the sensor without having to be paired. Scraping this data is quite simple, and the GitHub page includes a breakdown of what each byte in the broadcast message means. Avoiding direct connections not only makes it easier to quickly read the values from multiple thermometers, but should keep the device’s CR2032 battery going for longer.

But perhaps the most impressive part of this project is how you get the custom firmware installed. You don’t need to crack the case or solder up a programmer. Just load the flasher page on a computer and browser combo that supports Web Bluetooth (a smartphone is probably the best bet), point it to the MAC address of the thermometer you want to flash, and hit the button. [Aaron] is no stranger to developing user-friendly OTA installers for his firmware projects, but even for him, it’s quite impressive.

Continue reading “Custom Firmware For Cheap Bluetooth Thermometers”