I’ve noticed that we hear a lot less from corporate research labs than we used to. They still exist, though. Sure, Bell Labs is owned by Nokia and there is still some hot research at IBM even though they quit publication of the fabled IBM Technical Disclosure Bulletin in 1998. But today innovation is more likely to come from a small company attracting venture capital than from an established company investing in research. Why is that? And should it be that way?

The Way We Were

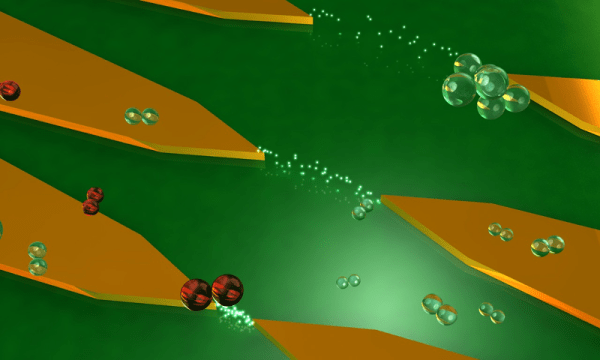

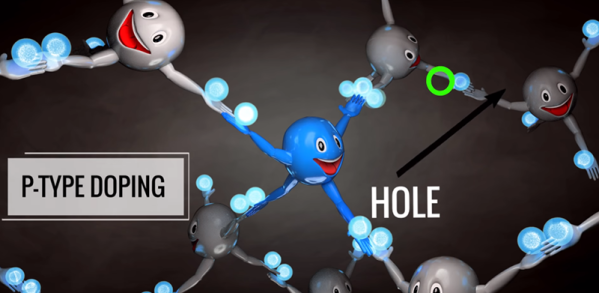

There was a time when every big company had a significant research and development arm. Perhaps the most famous of these was Bell Labs. Although some inventions are inevitably disputed, Bell Labs can claim radio astronomy, the transistor, the laser, Unix, C, and C++ among other innovations. They also scored a total of nine Nobel prizes.

Bell Labs had one big advantage: for many years it was part of a highly profitable monopoly, so perhaps the drive to make money right away was less than at other labs. Also, I think, times were different and businesses often had the ability to look past the next quarter.

Continue reading “Bell Labs, Skunk Works, And The Crowd Sourcing Of Innovation”