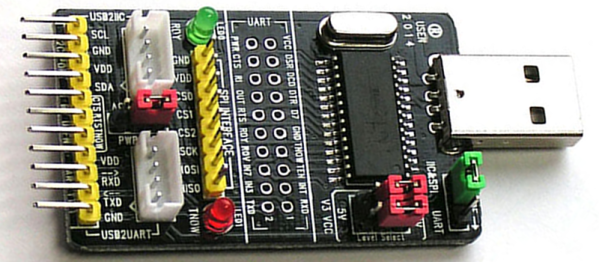

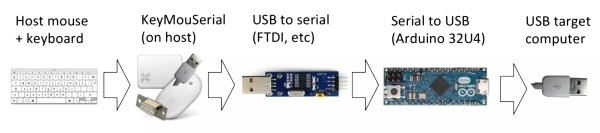

Debugging with printf is something [StorePeter] has always found super handy, and as a result he’s always been interested in tweaking the process for improvements. This kind of debugging usually has microcontrollers sending messages over a serial port, but in embedded development there isn’t always a hardware UART, or it might already be in use. His preferred method of avoiding those problems is to use a USB to Serial adapter and bit-bang the serial on the microcontroller side. It was during this process that it occurred to [StorePeter] that there was a lot of streamlining he could be doing, and thanks to serial terminal programs that support arbitrary baud rates, he’s reliably sending debug messages over serial at 5.3 Mbit/sec, or 5333333 Baud. His code is available for download from his site, and works perfectly in the Arduino IDE.

The whole thing consists of some simple, easily ported code to implement a bare minimum bit-banged serial communication. This is output only, no feedback, and timing consists of just sending bits as quickly as the CPU can handle, leaving it up to the USB Serial adapter and rest of the world to handle whatever that speed turns out to be. On a 16 MHz AVR, transmitting one bit can be done in three instructions, which comes out to about 5333333 baud or roughly 5.3 Mbit/sec. Set a terminal program to 5333333 baud, and you can get a “Hello world” in about 20 microseconds compared to 1 millisecond at 115200 baud.

He’s got additional tips on using serial print debugging as a process, and he’s done a followup where he stress-tests the reliability of a 5.3 MBit/sec serial stream from an ATMega2560 at 16 MHz in his 3D printer, and found no missed packets. That certainly covers using printf as a debugger, so how about a method of using the debugger as printf?