One of the biggest reasons for playing older video games on original hardware is that emulators and modern controllers can’t replicate the exact feel of how those games would have been originally experienced. This is true of old PC games as well, so if you want to use your original Sidewinder steering wheel or antique Logitech joystick, you’ll need something like [Necroware]’s GamePort adapter to get them to communicate with modern hardware.

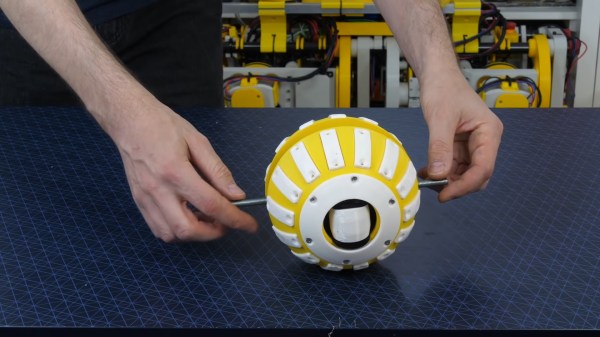

In a time before USB was the standard, the way to connect controllers to PCs was through the GamePort, typically found on the sound card. This has long since disappeared from modern controllers, so the USB interface [Necroware] built relies on an Arduino to do the translating. Specifically, the adapter is designed as a generic adapter for several different analog joysticks, and a series of DIP switches on the adapter select the appropriate mode. Check it out in the video after the break. The adapter is also capable of automatically calibrating the joysticks, which is necessary as the passive components in the controllers often don’t behave the same way now as they did when they were new.

Plenty of us have joysticks and steering wheels from this era stored away somewhere, so if you want to experience Flight Simulator 5.0 like it would have been experienced in 1993, all it takes is an Arduino. And, if you want to run these programs on bare metal rather than in an emulator, it is actually possible to build a new Intel 486 gaming PC, which operates almost exactly like a PC from the 90s would have.