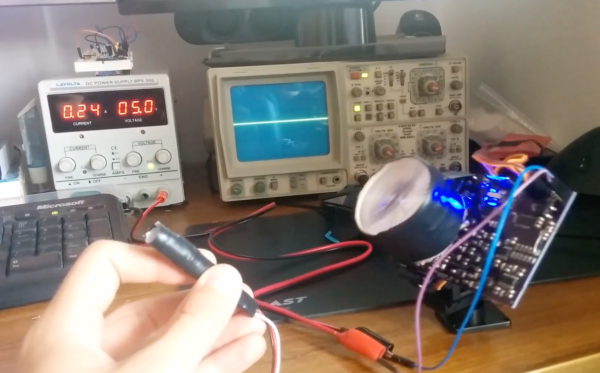

At the keynote for the Intel Developers Forum, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich introduced the Intel Joule compute module, a ‘maker board’ targeted at Internet of Things developers. The high-end board in the lineup features a quad-core Intel Atom running at 2.4 GHz, 4GB of LPDDR4 RAM, 16GB of eMMC, 802.11ac, Bluetooth 4.1, USB 3.1, CSI and DSI interfaces, and multiple GPIO, I2C, and UART interfaces. According to the keynote, the Joule module will be useful for drones, robotics, and with support for Intel’s RealSense technology, it may find a use in VR and AR applications. The relevant specs can be found on the Intel News Fact Sheet (PDF).

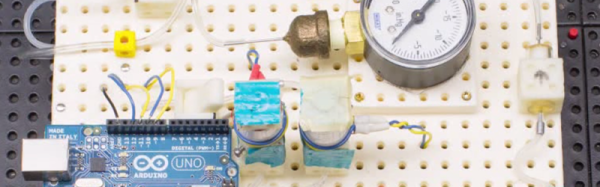

This is not Intel’s first offering to the Internet of Things. A few years ago, Intel partnered up with Arduino (the Massimo one) to produce the Intel Galileo. This board featured the Intel Quark SoC, a 400MHz, 32-bit Intel Pentium ISA processor. It was x86 in an Arduino format. This was quickly followed by the Intel Edison based on the same Quark SoC, which was followed by the Intel Curie, found in the Arduino 101 and this year’s DEF CON badge.

We’ve seen plenty of Intel’s ‘maker’ and Internet of Things offerings, but we haven’t seen these platforms succeed. You could spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in market research to determine why these platforms haven’t seen much success, but the Hackaday comments will tell you the same thing for free: the documentation for these platforms is sparse, and nobody knows how to make these boards work.

Perhaps because of the failures of Intel’s IoT market, the Joule differs significantly from previous offerings. Although it can be easily compared to the Raspberry Pi, Beaglebone, and a hundred other tiny single board computers, the official literature for the Joule makes a comparison between it and the Nvidia Jetson easy. The Nvidia Jetson is a high-power, credit card-sized ‘supercomputer’ meant to be a building block for high-performance applications, such as drones and anything that requires video or a very fast processor. The Joule fits into this market splendidly, with demonstrated applications including augmented reality safety glasses for Airbus employees and highway patrol motorcycle helmet displays. Here, the Joule might just find a market. This might even be the main focus of the Joule – it can be integrated onto Gumstix carrier boards, providing a custom single board computer with configurable displays, connectors, and sensors.

The Intel Joule lineup consists of the Joule 570x and 550x, with the 550x being a bit slower, a Gig less RAM, and half as much storage. They will be available in Q4 2016 from Mouser, Newegg, and other Intel reseller partners.