There’s a saying among writers that goes something like “Everyone has a novel in them, but in most cases that’s where it should stay”. Its source is the subject of some dispute, but it remains sage advice that wannabe authors should remember on dark and stormy nights.

It is possible that a similar saying could be constructed among hackers and makers: that every one of us has at least one motor vehicle within, held back only by the lack of available time, budget, and workshop space. And like the writers, within is probably where most of them should stay.

[TheFrostyman] might have had cause to heed such advice. For blessed with a workshop, a hundred dollars, and the free time of a 15-year-old, he’s built his first motorcycle. It’s a machine of which he seems inordinately proud, a hardtail with a stance somewhere closer to a café racer and powered by what looks like a clone of the ubiquitous Honda 50 engine.

Unfortunately for him, though the machine looks about as cool a ride as any 15-year-old could hope to own it could also serve as a textbook example of how not to build a safe motorcycle. In fact, we’d go further than that, it’s a deathtrap that we hope he takes a second look at and never ever rides. It’s worth running through some of its deficiencies not for a laugh at his expense but to gain some understanding of motorcycle design.

Continue reading “Fail Of The Week: How Not To Build Your Own Motorcycle”

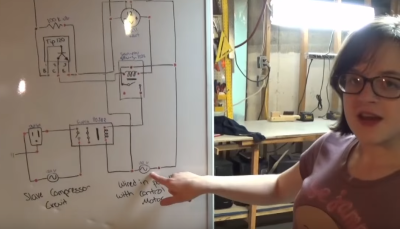

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.

The Arduino’s GPIO pins can’t handle 9 amp AC loads, so [Hannah] wired them to TIP120 transistors. The TIP120s drive low power relays, which in turn drive high current air conditioning relays. The system works quite well, as can be seen in the video below the break.