The appeal of adding Nixie tube displays to a project seems to know no end. First it was Nixie clocks, now it’s Nixie power meters, with the latest addition being this Nixie-Steampunk hybrid solar power monitor.

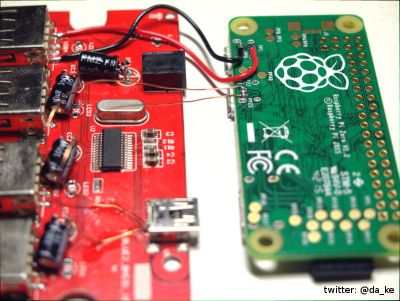

We’re suckers for a project with a vintage look, and this one pushes all the buttons. Built on commission for a solar power company CEO’s office, [Paul Parry]’s build is based on a Depression-era Metropolitan-Vickers combined voltmeter and ammeter. The huge meters with mirrored scales and the rich wood of the case – our guess is that it’s mahogany – made a great starting point, and after some careful hole drilling, nine IN-18 Nixies were sprouting from the case. A strip of RGB LEDs below decks added the requisite backlighting of the envelopes, and a Raspberry Pi was enlisted to interpret data from the company’s solar farm and drive the tubes and the meters. The project was capped off with a new finish on the case and a couple of fancy brass plaques.

[Paul] sent us the tip for his build after seeing the last power meter we covered, and we have to say they’re both great looking and functional projects. Keep the Nixie projects coming!

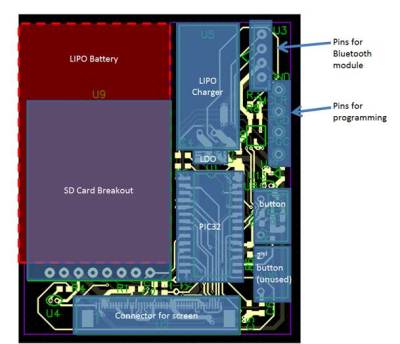

and meant one shot at getting his custom PCB right.

and meant one shot at getting his custom PCB right.