This is your last day to enter the 2017 Hackaday Prize. The theme is to Build Something that Matters, so don’t sit on the sidelines.

You have great power to make a change in the world. Put your mind to a problem you believe is worth solving and inspire us with your build. Whether it’s a turnkey solution or a seed idea that inspires those around you, let’s work on making the world a little bit better place. Get your entry for Anything Goes in by Monday morning.

As Entries Close, Finalists Polish Their Projects

![]()

There have been five challenge rounds of the Hackaday Prize and we’ve seen more than 1000 entries. From each round, 20 finalists were chosen who were awarded $1000 each but we’re just getting started. The top five prizes totaling $75,000 still remain.

A panel of fantastic Hackaday Prize Judges will begin reviewing the final round projects on October 21st. Finalists are continuing to refine their projects since being selected, adding project logs, a bill of material, design files, and a project video. This all leads to the awarding of the Grand Prize on Saturday, November 11th at the Hackaday Superconference.

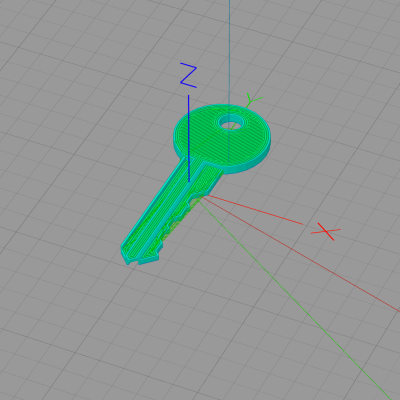

Rather than simply duplicating an existing key, [Dave] created a parametric key blank in OpenSCAD; he just enters his pin settings and the model generator creates the print file. He printed ABS on a glass plate with a schmeer of acetone on it, and .15mm layer heights. Another reason [Dave] chose Kwikset is that the one he had was super old and super loose — he theorizes that a newer, tighter lock might simply break the key.

Rather than simply duplicating an existing key, [Dave] created a parametric key blank in OpenSCAD; he just enters his pin settings and the model generator creates the print file. He printed ABS on a glass plate with a schmeer of acetone on it, and .15mm layer heights. Another reason [Dave] chose Kwikset is that the one he had was super old and super loose — he theorizes that a newer, tighter lock might simply break the key.