It’s now possible to not only see people through walls but to see how they’re moving and if they’re walking, to tell who they are. We finally have the body scanner which Schwarzenegger walked behind in the original Total Recall movie.

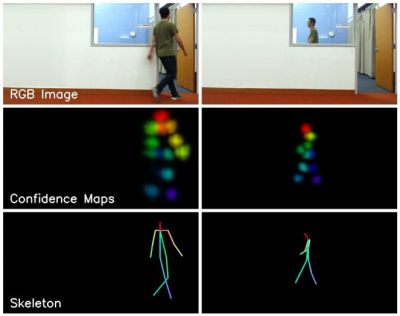

This is the work of a group at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). The seeing-through-the-wall part is done using an RF transmitter and receiving antennas, which isn’t very new. Our own [Gregory L. Charvat] built an impressive phased array radar in his garage which clearly showed movement of complex shapes behind a wall. What is new is the use of neural networks to better decipher what’s received on those antennas. The neural networks spit out pose estimations of where people’s heads, shoulders, elbows, and other body parts are, and a little further processing turns that into skeletal figures.

This is the work of a group at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). The seeing-through-the-wall part is done using an RF transmitter and receiving antennas, which isn’t very new. Our own [Gregory L. Charvat] built an impressive phased array radar in his garage which clearly showed movement of complex shapes behind a wall. What is new is the use of neural networks to better decipher what’s received on those antennas. The neural networks spit out pose estimations of where people’s heads, shoulders, elbows, and other body parts are, and a little further processing turns that into skeletal figures.

They evaluated its accuracy in a number of ways, all of which are detailed in their paper. The most interesting, or perhaps scariest way was to see if it could tell who the skeletal figures were by using the fact that each person walks with their own style. They first trained another neural network to recognize the styles of different people. They then pass the pose estimation output to this style-recognizing neural network and it correctly guessed the people with 83% accuracy both when they were visible and when they were behind walls. This means they not only have a good idea of what a person is doing, but also of who the person is.

Check out the video below to see some pretty impressive side-by-side comparisons of live action and skeletal versions doing all sorts of things under various conditions. It looks like the science fiction future in Total Recall has gotten one step closer. Now if we could just colonize Mars.

Continue reading “Using An AI And WiFi To See Through Walls”