Ceiling fans seem to be an oft-misunderstood or overlooked household appliance. As such, they seem to have missed a lot of the IoT wave. Sure, you can get smart controllers for them to plug into your home automation system of choice, but these mostly rely on temperature sensors, simple timers, or voice commands. There’s a lot more to a ceiling fan than maintaining a comfortable temperature, as [EJ] demonstrates with this smarter ceiling fan build.

A big part of the job of a ceiling fan is to improve air circulation, which can help a room from feeling “stuffy”. This feeling is usually caused by excess CO2 as a result of respiration in an area where the air is not moving enough to exhaust this gas. Not only does [EJ]’s controller make use of a temperature monitor for controlling the fan automatically, but there is also a CO2 sensor integrated to improve this aspect of air quality when needed.

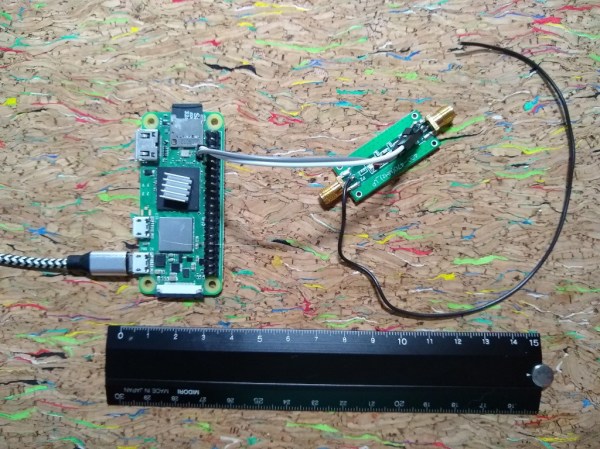

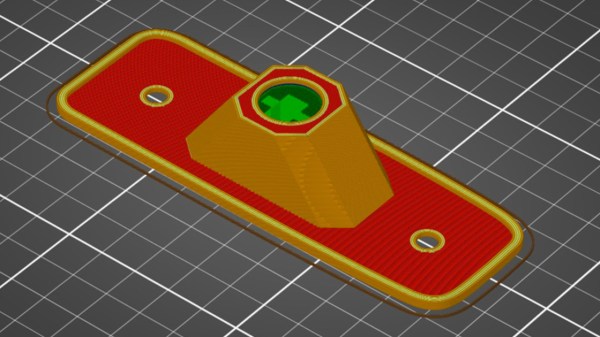

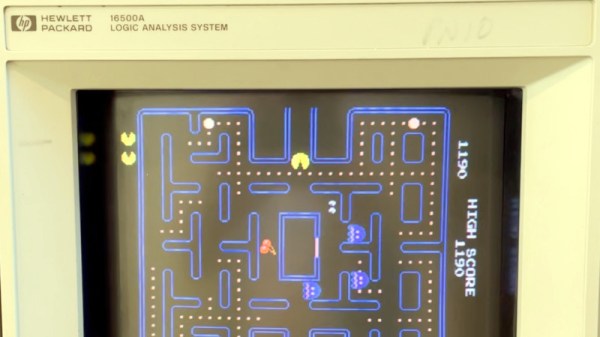

The entire build is based on a Raspberry Pi Zero, and nothing needed to be changed about the ceiling fan itself for this added functionality because it already included a radio-based remote control. With some monitoring of the signals produced by the remote, the Raspberry Pi was programmed to mimic these commands when the surrounding sensors captured a condition where [EJ] would want the fan on. There’s also a manual control button as well, so the fan control is not entirely in the hands of the computer.

For a little more detailed information about this build, there’s a separate project page which details a lot of the information about the RF waveform capturing and recreation. And, if you want to take your fan to the next level, take a look at this one which focuses on building a smartphone app to control the fan instead.