Engineering student and DIY enthusiast [Xasin] thought that the usual ways of controlling various home devices, such as phone apps and web interfaces, were too boring. Instead, he developed the wearable Tap interface which is a cross between a Star Trek comms badge and mobile holo-emitter. The basic idea is to control stuff by tapping the pendant. But things got a little out of hand since this project started two years ago.

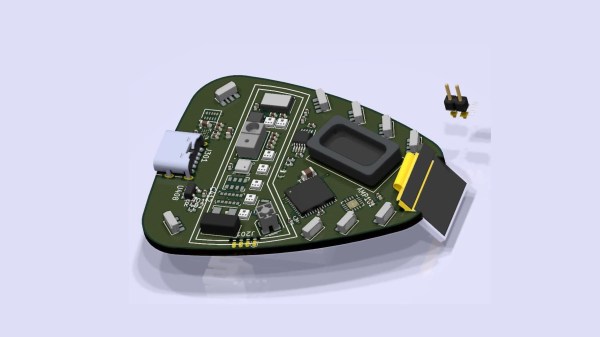

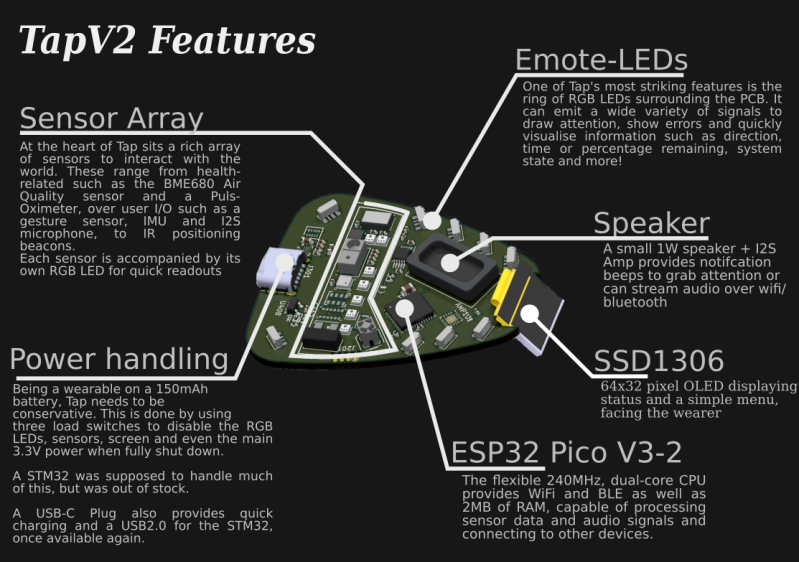

[Xasin] began with Tap version 1 back in 2019, and learned all about coding for BLE, making 3D printed cases, and eventually working out all the kinks in the system. Tap v1 used capacitive touch sensing, but the current version detects physical taps using an accelerometer and also can detect gestures. Feature creep along the way brings a sensor array, an array of emotive LEDs, an OLED screen, and a speaker. The whole thing is powered by a dual-core ESP32 Pico MCU. [Xasin] has published his project on GitHub in case you want to explore some of these other features on your own.

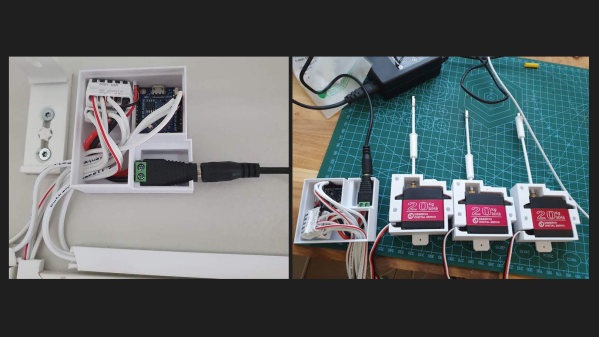

The project is only partially up and running because a few critical components are unavailable due to the global parts shortage. But it will soon be able to control smart home devices, such as [Xasin]’s standalone Dragon’s Home smart home system that we wrote about earlier this year. If you want to learn more about tap controlling in general, check out this article from 2018. You can see the Tap introduce itself and its features in the short video below the break.