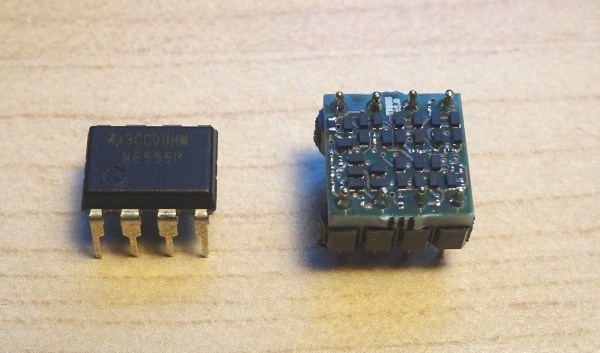

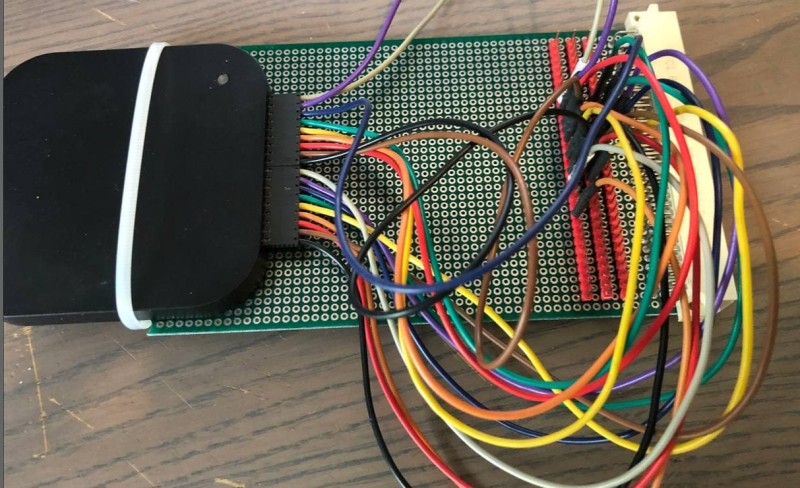

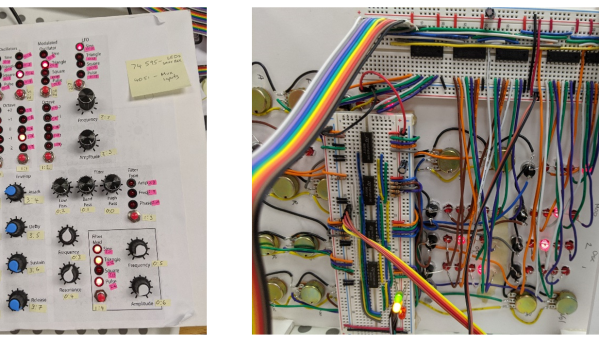

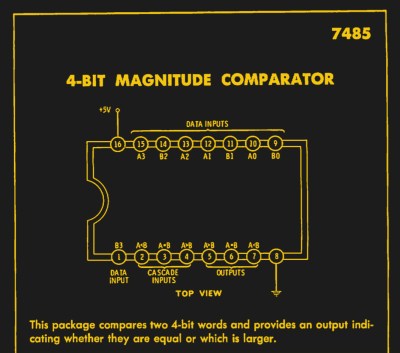

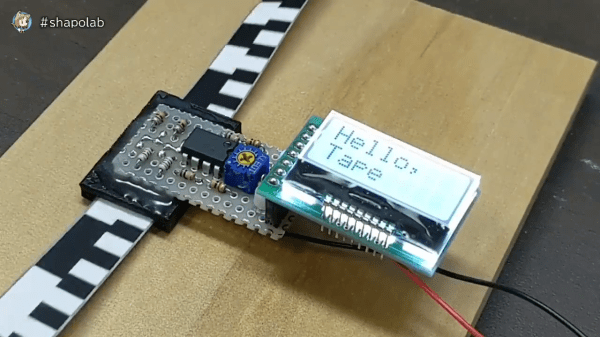

Over at Tiny Transistor labs, [Robo] took it upon himself to reproduce the classic 555 timer in discrete transistor form. For bonus points, he also managed to put it in a package that’s the same basic size, pin compatible with, and a plug-in replacement for the original. The first task was deciding which 555 circuit to implement. He examined a handful of different implementations — and by examined, we mean dissected them and studied the die circuitry under a microscope. In the end, he went with Hans Camenzind’s original circuit, both as a tribute and because it used the fewest transistors — a point which helped manage the final size, which is only a little bit bigger than the IC!

Speaking of sizes, have you ever soldered an EIA 01005 resistor? We agree with [mbedded.ninja] who wrote on a post about standard chip resistor sizes, the 01005 is a “ridiculously small chip package that can barely be seen by the naked eye.” It is 16 thou x 8 thou (0.4 mm x 0.2 mm) in size, and despite its name and placement in the Imperial series, it is not half the size of an 0201. The transistors are your standard 2N3904 / 2N3906, but purchased in a not-so-standard DFN (Dual Flat Pack, No Leads). We might think a 1.0 x 0.6 mm component as small, but compared to its neighboring resistors in this circuit, it’s huge.

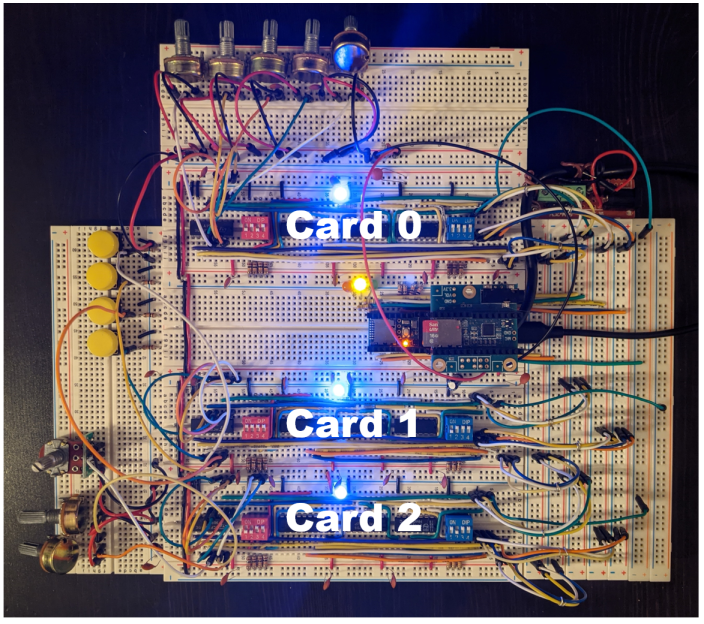

[Robo] has done this kind of project before, most recently making a discrete recreation of of the classic 741 op-amp. We covered a similar, but larger, discrete 555 timer project back in 2011. If you want to go really big-scale with your own reproduction project, check out the MOnSter 6502 from five years ago for further inspiration. Thanks to [Lucas] for the tip.