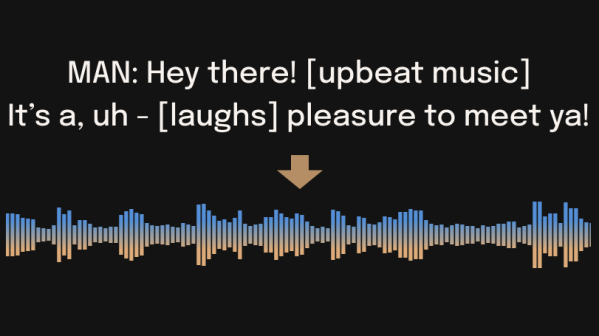

Bark is a universal text-to-audio model that can not only create realistic speech, it can incorporate music, background noises, and sound effects. It can even include non-speech sounds like laughter, sighs, throat clearings, and similar elements. But despite the fact that it can deliver such complex results, it’s important to understand some of the peculiarities.

Bark is not a conventional text-to-speech program, and how it works has a lot more in common with large language model AI chatbots. This means that results can deviate from expectations, and outputs aren’t necessarily going to be studio-quality speech. As the project’s README points out, “(generated outputs can) be anything from perfect speech to multiple people arguing at a baseball game recorded with bad microphones.” That being said, there is some support for voice presets as a way to help guide the model with some consistency.

Bark was designed by a company called Suno for research purposes and is available under the MIT License. It can be installed and run locally, and has some demos available as well as an online implementation.

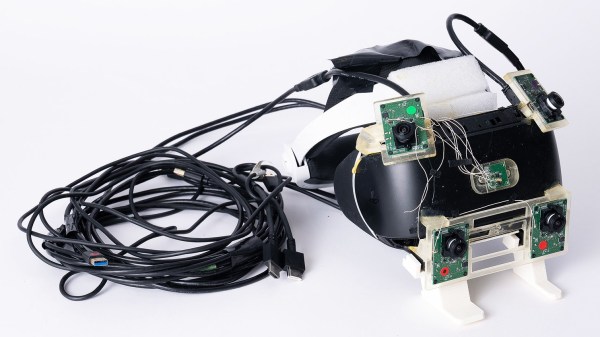

The ability to install and run Bark locally is promising territory for incorporating it into projects. And should you be more interested in speech-to-text instead, don’t forget about this plain C/C++ implementaion of AI-powered speech recognition.