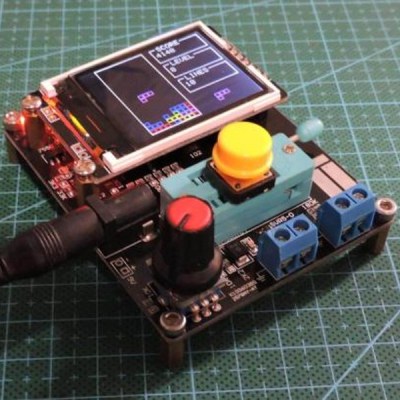

You know how it is. You’re working on a project that needs to move air or water, or move through air or water, but your 3D design chops and/or your aerodynamics knowledge hold you back from doing the right thing? If you use OpenSCAD, you have no excuse for creating unnecessary turbulence: just click on your favorite foil and paste it right in. [Benjamin]’s web-based utility has scraped the fantastic UIUC airfoil database and does the hard work for you.

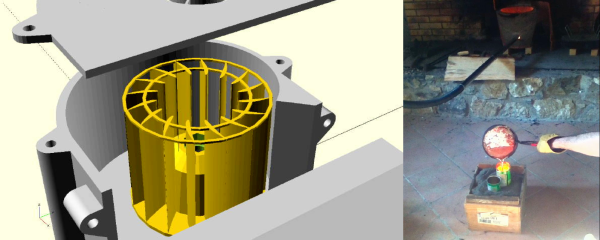

While he originally wrote the utility to make the blades for a blower for a foundry, he’s also got plans to try out some 3D printed wind turbines, and naturally has a nice collection of turbine airfoils as well.

If your needs aren’t very fancy, and you just want something with less drag, you might also consider [ErroneousBosch]’s very simple airfoil generator, also for OpenSCAD. Making a NACA-profile wing that’s 120 mm wide and 250 mm long is as simple as airfoil_simple_wing([120, 0030], wing_length=250);

If you have more elaborate needs, or want to design the foil yourself, you can always plot out the points, convert it to a DXF and extrude. Indeed, this is what we’d do if we weren’t modelling in OpenSCAD anyway. But who wants to do all that manual labor?

Between open-source simulators, modelling tools, and 3D printable parts, there’s no excuse for sub-par aerodynamics these days. If you’re going to make a wind turbine, do it right! (And sound off on your favorite aerodynamics design tools in the comments. We’re in the market.)