Not a hack, but something we’ve been wanting to see forever is open access to all scientific publications. If we can soapbox for a few seconds, it’s a crying shame that most academic science research is funded by public money, and then we’re required to pay for it again in the form of journal subscriptions or online payments if we want to read it. We don’t like science being hidden behind a paywall, and neither do the scientists whose work is hidden from wider view.

Here are two heartening developments: Unpaywall is a browser extension that automates the search for pre-press versions of a journal article, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are denying rights to research that it has funded if the resulting publications aren’t free and open.

The concept of “publishing” pre-print versions of academic papers before publication is actually older than the World Wide Web — the first versions of what would become arXiv.org shared LaTeX version of physics papers and ran on FTP and Gohper. The idea is that by pushing out a first version of the work, a scientist can get early feedback and lay claim to interesting discoveries prior to going through the long publication process. Pre-prints are available in many other fields now, and all that’s left for you to do is search for them. Unpaywall searches for you.

Needless to say, this stands to take a chunk out of the pocketbooks of scientific publishers. (Whether this matters in comparison to the large fees that they charge libraries, universities, and other institutional subscribers is open to speculation.) The top-tier journals — Nature, Science, the New England Journal of Medicine, and others — have been reluctant to offer open access, so brilliant scientists are faced with the choice of making their work openly available or publishing in a prestigious journal, which is good for their career.

In a step to change the status quo, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation took their ball and went home; research funded with their money has to be open-access, period. We think that’s a laudable development, and assuming that the foundation funds quality research, the top-tier journals will be losing out unless they cooperate.

To be fair to the journal publishers, many journals are open-access or have open-access options available. The situation today is a lot better than it was even five years ago. But if we had a dime for every time we try to research some scientific paper and ran into a paywall, we wouldn’t be reduced to hawking snazzy t-shirts.

Thanks [acs] for the tip!

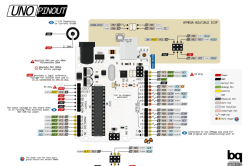

We all love [pighixx]’s pinout diagrams. Here’s his take on the Arduino Uno, for instance. It turns out that he does these largely by hand. That’s art for ya.

We all love [pighixx]’s pinout diagrams. Here’s his take on the Arduino Uno, for instance. It turns out that he does these largely by hand. That’s art for ya.