In this era of 4K UHD game console graphics and controllers packed full of buttons, triggers, and joysticks, it’s good to occasionally take a step back from the leading edge. Take a breath and remind ourselves that we don’t always need all those pixels and buttons to have some fun. The LedCade is a μ (micro) arcade game cabinet built by [bobricius] for just this kind of minimalist gaming.

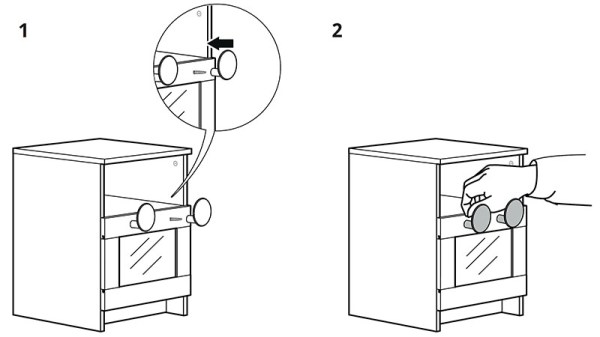

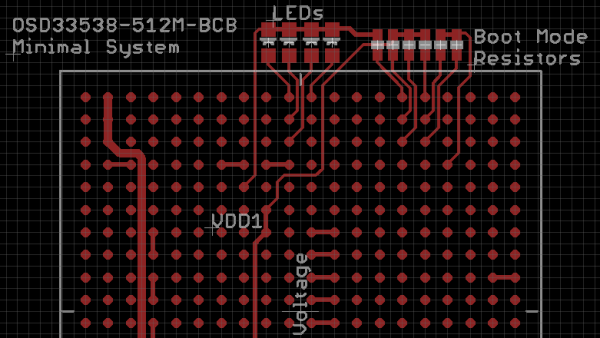

Using just three buttons for input and an 8×8 LED matrix for output, the LedCade can nevertheless play ten different games representing classic genres of retro arcade gaming. And in a brilliant implementation of classic hardware hacking humor, a player starts their game by inserting not a monetary coin but a CR2032 coin cell battery.

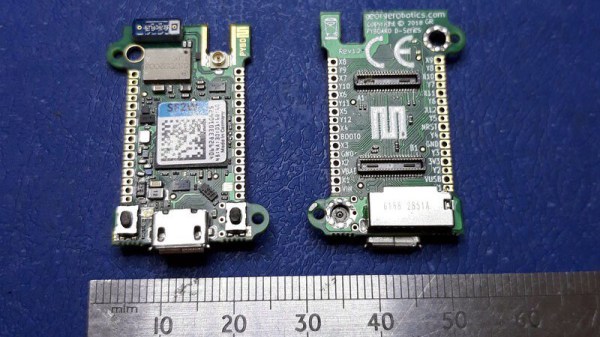

Behind the screen is a piezo speaker for appropriately vintage game sounds, and an ATmega328 with Arduino code orchestrating the fun. [bobricius] is well practiced at integrating all of these components as a result of developing an earlier project, the single board game console. This time around, the printed circuit board goes beyond being the backbone, the PCB sheet is broken apart and reformed as the enclosure. With classic arcade cabinet proportions, at a far smaller scale.

If single player minimalist gaming isn’t your thing, check out this head-to-head gaming action on 8×8 LED arrays. Or if you prefer your minimalist gaming hardware to be paper-thin, put all the parts on a flexible circuit as the Arduflexboy does.