Sony’s video game division is gearing up for their upcoming PlayStation 5, pushing its predecessor PlayStation 4 off the spotlit pedestal. One effect of this change is Sony ever so slightly relaxing secrecy surrounding the PS4, allowing [Nikkei Asian Review] inside a PlayStation 4 final assembly line.

This article was written to support Sony and PlayStation branding for a general audience, thus technical details are few and far in between. This shouldn’t be a huge surprise given how details of mass production can be a competitive advantage and usually kept as trade secrets by people who knew to keep their mouths shut. Even so, we get a few interesting details accompanied by many quality pictures. Giving us a glimpse into an area that was formerly off-limits to many Sony employees never mind external cameras.

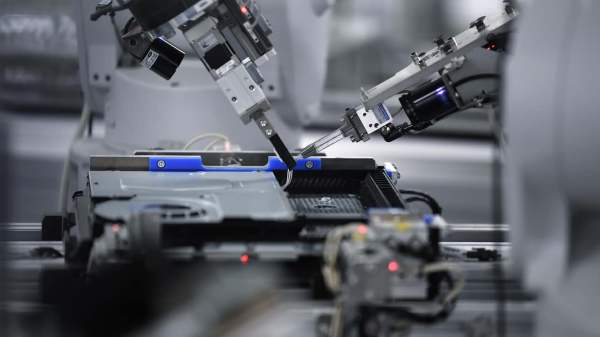

The quoted engineers are proud of their success coaxing robots to assemble soft and flexible objects, and rightly so. Generally speaking robots have a hard time handling non-rigid objects, but this team has found ways to let their robots handle the trickier parts of PS4 assembly. Pick up wiring bundles and flat ribbon cables, then plug them into circuit board connectors with appropriate force. Today’s automated process is the result of a lot of engineers continually evolving and refining the system. The assembly machines are covered with signs of those minds at work. From sharpie markers designating positive and negative travel directions for an axis, to reminders written on Post-It notes, to assembly jig parts showing the distinct layer lines of 3D printing.

The quoted engineers are proud of their success coaxing robots to assemble soft and flexible objects, and rightly so. Generally speaking robots have a hard time handling non-rigid objects, but this team has found ways to let their robots handle the trickier parts of PS4 assembly. Pick up wiring bundles and flat ribbon cables, then plug them into circuit board connectors with appropriate force. Today’s automated process is the result of a lot of engineers continually evolving and refining the system. The assembly machines are covered with signs of those minds at work. From sharpie markers designating positive and negative travel directions for an axis, to reminders written on Post-It notes, to assembly jig parts showing the distinct layer lines of 3D printing.

We love seeing the result of all that hard work, but lament the many interesting stories still untold. We would have loved a video showing the robots in action. For that, the record holder is still Valve who provided an awesome look at the assembly of the Steam Controller that included a timelapse of the assembly line itself being assembled. If you missed that the first time, around, go watch it right now!

At least we know how to start with the foundations: everything we see on this PS4 assembly line is bolted to an aluminum extrusion big or small. These building blocks are useful whether we are building a personal project or a video console final assembly line, so we’ve looked into how they are made and how to combine them with 3D printing for ultimate versatility.

[via Adafruit]