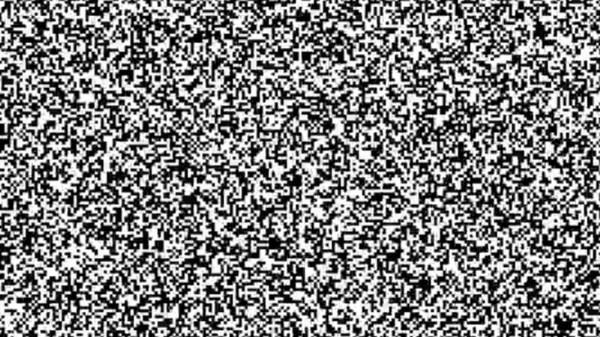

It’s the most basic of functions for a camera, that when you point it at a scene, it produces a photograph of what it sees. [Jasper van Loenen] has created a camera that does just that, but not perhaps in the way we might expect. Instead of committing pixels to memory it takes a picture, uses AI to generate a text description of what is in the picture, and then uses another AI to generate an image from that picture. It’s a curiously beautiful artwork as well as an ultimate expression of the current obsession with the technology, and we rather like it.

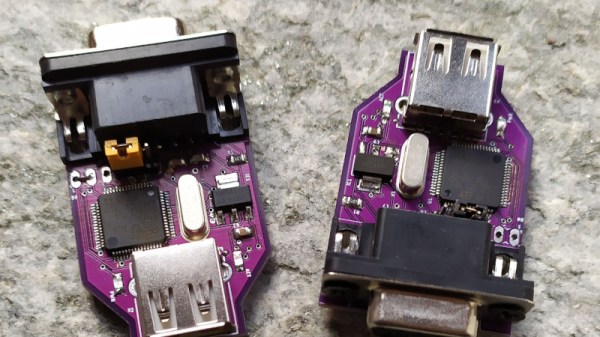

The camera itself is a black box with a simple twin-lens reflex viewfinder. Inside is a Raspberry Pi that takes the photo and sends it through the various AI services, and a Fuji Instax Mini printer. Of particular interest is the connection to the printer which we think may be of interest to quite a few others, he’s reverse engineered the Bluetooth protocols it uses and created Python code allowing easy printing. The images it produces are like so many such AI-generated pieces of content, pretty to look at but otherworldly, and weird parallels of the scenes they represent.

It’s inevitable that consumer cameras will before long offer AI augmentation features for less-competent photographers, meanwhile we’re pleased to see Jasper getting there first.