Sometimes here at Hackaday we bring you stories from slightly outside our world of tech, because they have an interesting angle. Maybe they relate to science or astronomy, or in the case of the UK’s Ordnance Survey explaining how Britain’s three Norths will align, geography.

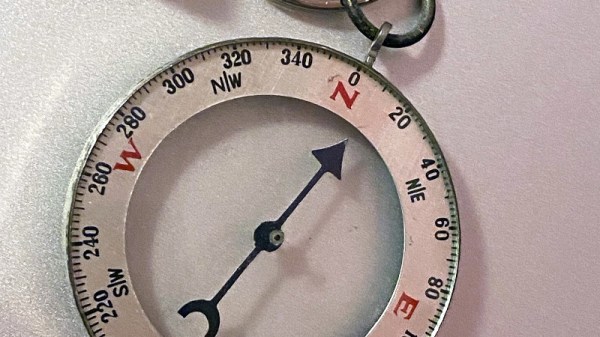

Some of you may know that the British monarch has two birthdays, but three Norths, what on earth is going on? You’ll guess that two of them are true North, pointing to the North Pole, and magnetic North, pointing to the Earth’s north magnetic field, but how about the third? It’s grid North — the north of the country’s mapping grid system in which the curved surface is projected onto a flat sheet.

It aligns with true North at 2 degrees West of Greenwich, and the news is that for the first time ever due to movement of the magnetic North Pole, the three different Norths will align at a point in the south of England. Magnetic North has been on the move at some pace over the last few decades, from a position somewhere in the Canadian Arctic islands northwards, and it so happens that for Brits its direction is briefly aligned with our view of the Pole. The Ordnance Survey story is of some interest, but for a wealth of information it’s worth consulting NASA. Take a look at the video below the break.

Continue reading “Three Norths Align, And It’s Not Even Up North”