We live in a connected world, but that world ends not far beyond the outermost cell phone tower. [John Grant] wants to be connected everywhere, even in regions where no mobile network is available, so he is building a solar powered, handheld satellite messenger: The MyComm – his entry for the Hackaday Prize.

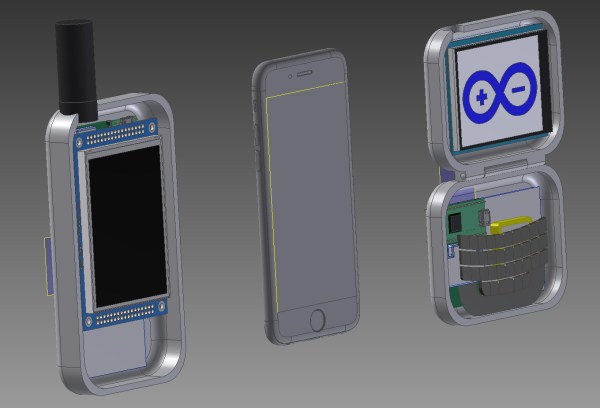

The MyComm is a handheld touch-screen device, much like a smartphone, that connects to the Iridium satellite network to send and receive text messages. At the heart of his build, [John] uses a RockBLOCK Mk2 Iridium SatComm Module hooked up to a Teensy 3.1. The firmware is built upon a FreeRTOS port for proper task management. Project contributor [Jack] crafted an intuitive GUI that includes an on-screen keyboard to write, send and receive messages. A micro SD card stores all messages and contact list entries. Eventually, the system will be equipped with a solar cell, charging regulator and LiPo battery for worldwide, unconditional connectivity.

2016 will be an interesting year for the Iridium network since the first satellites for the improved (and backward-compatible) “Iridium NEXT” network are expected to launch soon. At times the 66 Iridium satellites currently covering the entire globe were considered a $5B heap of space junk due to deficiencies in reliability and security. Yet, it’s still there, with maker-friendly modems being available at $250 and pay-per-use rates of about 7 ct/kB (free downstream for SDR-Hackers). Enjoy the video of [Jack] explaining the MyComm user interface:

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: MyComm Handheld Satellite Messenger”