While some might say we’re living in a cyberpunk future already, one technology that’s conspicuously absent is wetware. The Unconventional Computing Laboratory is working to change that.

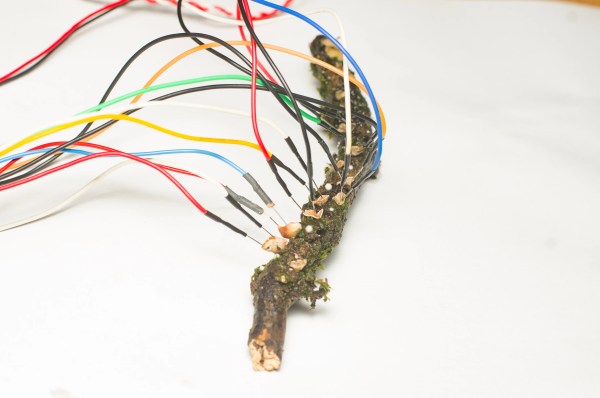

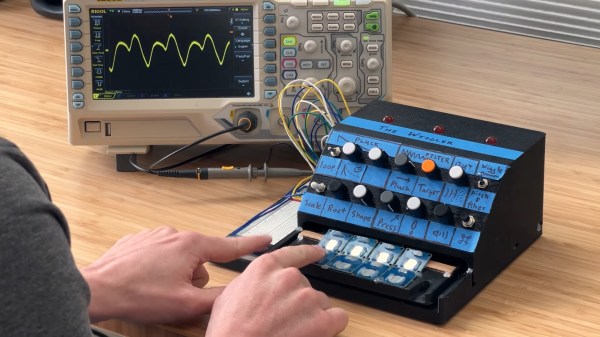

Previous work with slime molds has shown useful for spatial and network optimization, but mycelial networks add the feature of electrical spikes similar to those found in neurons, opening up the possibility of digital computing applications. While the work is still in its early stages, the researchers have already shown how to create logic gates with these fantastic fungi.

Long-term, lead researcher [Andrew Adamatzky] says, “We can say I’m planning to make a brain from mushrooms.” That goal is quite awhile away, but using wetware to build low power, self-repairing fungi devices of lower complexity seems like it might not be too far away. We think this might be applicable to environmental sensing applications since biological systems are likely to be sensitive to many of the same contaminants we humans care about.

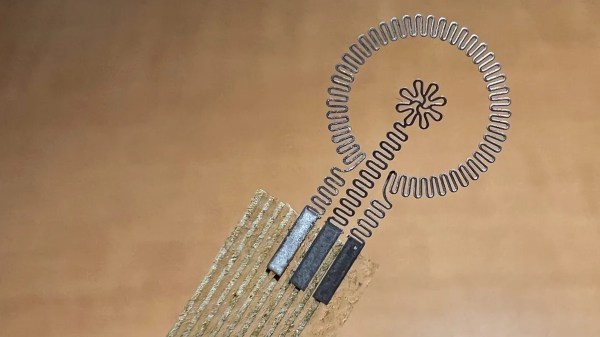

We’ve seen a other efforts in myceliotronics, including biodegradable PCB substrates and attempts to send sensor signals through a mycelial network.

Via Tom’s Hardware.