There’s no point in denying it — if you’re a regular reader of Hackaday, you’ve almost certainly got a favorite chip. Some in the audience yearn for the simpler days of the 6502, while others spend their days hacking on modern microcontrollers like the ESP32 or RP2040. There are even some of you out there still reaching for the classic 555. Whatever your silicon poison, there’s a good chance the Macrochips project from [Jason Coon] has supersized it for you.

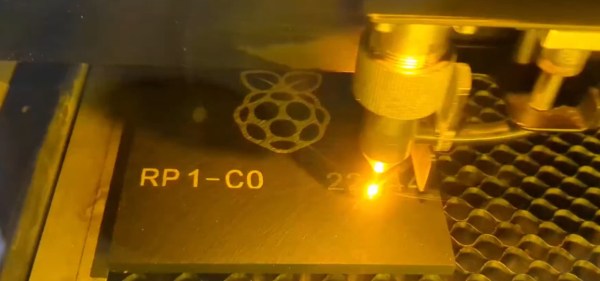

The idea is simple: get a standard 100 mm x 100 mm (4″ x 4″) slate coaster, throw it in your laser engraver of choice, and zap it with a replica of a chip’s label. The laser turns the slate a light gray, which, when contrasted with the natural color of the slate, makes for a fairly close approximation of what the real thing looks like. To date, [Jason] has given more than 140 classic and modern chips the slate treatment. Though he’s only provided the SVGs for a handful of them, we’re pretty sure anyone with a laser at home will have the requisite skills to pull this off without any outside assistance.

The page credits a post from [arturo182] for the idea (Nitter), which pointed out a slate RP2040 hiding out on the corner of [Graham Sanderson]’s desk back in 2021. We just became aware of the trend when [Jason] posted his freshly engraved RP1 on Mastodon in honor of the release of the Raspberry Pi 5.