Copyright law is a triple-edged sword. Historically, it has been used to make sure that authors and rock musicians get their due, but it’s also been extended to the breaking point by firms like Disney. Strangely, a concept that protected creative arts got pressed into duty in the 1980s to protect the writing down of computer instructions, ironically a comparatively few bytes of BIOS code. But as long as we’re going down this strange road where assembly language is creative art, copyright law could also be used to protect the openness of software as well. And doing so has given tremendous legal backbone to the open and free software movements.

So let’s muddy the waters further. Looking at cases like the CDDB fiasco, or the most recent sale of ADSB Exchange, what I see is a community of people providing data to an open resource, in the belief that they are building something for the greater good. And then someone comes along, closes up the database, and sells it. What prevents this from happening in the open-software world? Copyright law. What is the equivalent of copyright for datasets? Strangely enough, that same copyright law.

Data, being facts, can’t be copyrighted. But datasets are purposeful collections of data. And just like computer programs, datasets can be licensed with a restrictive copyright or a permissive copyleft. Indeed, they must, because the same presumption of restrictive copyright is the default.

I scoured all over the ADSB Exchange website to find any notice of the copyright / copyleft status of their dataset taken as a whole, and couldn’t find any. My read is that this means that the dataset is the exclusive property of its owner. The folks who were contributing to ADSB Exchange were, as far as I can tell, contributing to a dataset that they couldn’t modify or redistribute. To be a free and open dataset, to be shared freely, copied, and remixed, it would need a copyleft license like Creative Commons or the Open Data Commons license.

So I’ll admit that I’m surprised to have not seen permissive licenses used around community-based open data projects, especially projects like ADSB Exchange, where all of the software that drives it is open source. Is this just because we don’t know enough about them? Maybe it’s time for that to change, because copyright on datasets is the law of the land, no matter how absurd it may sound on the face, and the closed version is the default. If you want your data contributions to be free, make sure that the project has a free data license.

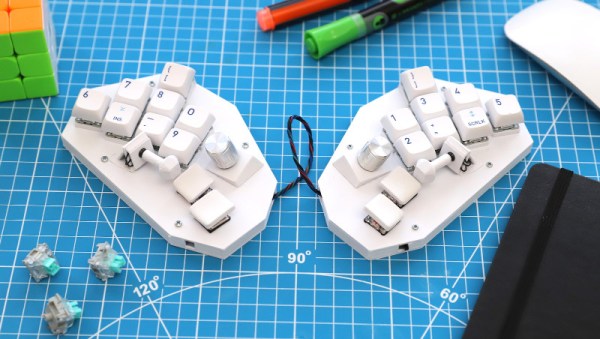

The solution is Fulcrum, a chording keyboard with keys that can be pressed with minimal movement. And one more clever trick is a thumb joystick, mounted in the thumb’s opposable orientation. It’s a 5-way switch, making for a bunch of combinations. The base model is a 20-key arrangement, and he’s also designed a larger, 40-key option.

The solution is Fulcrum, a chording keyboard with keys that can be pressed with minimal movement. And one more clever trick is a thumb joystick, mounted in the thumb’s opposable orientation. It’s a 5-way switch, making for a bunch of combinations. The base model is a 20-key arrangement, and he’s also designed a larger, 40-key option.

Overall, the design is very similar to the Pez Shooter, a long-discontinued Pez dispenser design. It uses a basic pistol form factor, and accepts a magazine of Pez pellets loaded into the grip. The magazine itself is cut out of a regular Pez dispenser, to avoid reinventing the wheel. Pulling the trigger fires the Pez pellets with spring power, launching candy into the air.

Overall, the design is very similar to the Pez Shooter, a long-discontinued Pez dispenser design. It uses a basic pistol form factor, and accepts a magazine of Pez pellets loaded into the grip. The magazine itself is cut out of a regular Pez dispenser, to avoid reinventing the wheel. Pulling the trigger fires the Pez pellets with spring power, launching candy into the air.