We’ve seen a lot of environmental monitoring projects here at Hackaday. Seriously, a lot. They usually take the form of a microcontroller, a couple sensors, and maybe a 3D printed case to keep it all protected. They’re pretty similar functionally as well, with the only variation usually coming in the protocol used to communicate their bits of collected data.

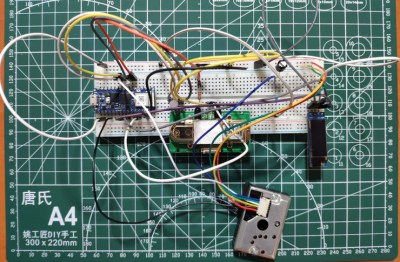

But even when compared with such an extensive body of previous work, this Jigglypuff IoT environmental monitor created by [Kutluhan Aktar] is pretty unusual. Sure, the highlights are familiar. Its MH-Z14A NDIR CO2 sensor and GP2Y1010AU0F optical dust detector are read by a WiFi-enabled microcontroller, this time the Arduino Nano RP2040 Connect, which ultimately reports its findings to the user via Telegram bot. There’s even a common SSD1306 OLED display on the unit to show the data locally. All things we’ve seen in some form or another in the past.

So what’s different? Well, it’s all been mounted to a huge Pokémon PCB, obviously. Even if you aren’t a fan of the pocket monsters, you’ve got to appreciate that bright pink solder mask. Honestly, the whole presentation is a great example of the sort of PCB artwork we rarely see outside of the BadgeLife scene.

Admittedly, there’s a lot easier ways to get notified about the air quality inside your house. We’re also not saying that haphazardly mounting your electronics onto a PCB designed to look like a character from a nearly 20+ year old Game Boy game is necessarily a great idea from a reliability standpoint. But if you were going to do something like that, then this project is certainly the one to beat.