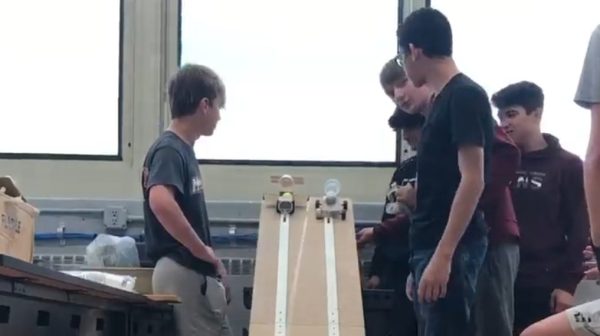

Pinewood derby racing is a popular pastime for scouting groups and many others besides. [Mr Coster] whipped up his own track with the assistance of some 3D printed parts, and used it to run a competition with a fun twist on the usual theme.

The track starts with a pair of MDF panels, on to which some strips are placed to act as guides for the racers. There’s also a release mechanism built with hinges and a pair of dowels that ensures both racers start the competition at exactly the same time. To give the track a nice transition from the downward slope to the horizontal, a series of curved transition pieces were designed in Fusion 360, 3D printed, and added to the course.

As for the competition, [Mr Coster] decided to eschew the usual focus on outright speed. Instead, students were charged with building the slowest possible car that could still complete the course. Just for the fun of it, though, the kids were then given one day to modify their slowest cars to compete in a more typical fastest-wins event. It gives the students a great lesson in optimizing for different performance parameters.

You might be old-school, though, and want to ruin the fun by taking it all way too seriously. Those competitors may wish to consider some of the advanced equipment we’ve featured before. Alternatively, you could run a no-holds-barred cheater’s version of the contest. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Slow Races On A Pinewood Derby Track Built From Scratch”