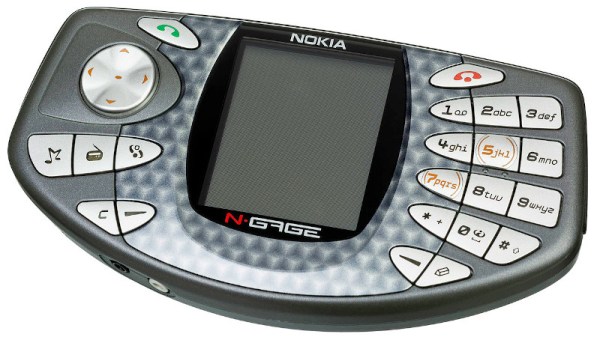

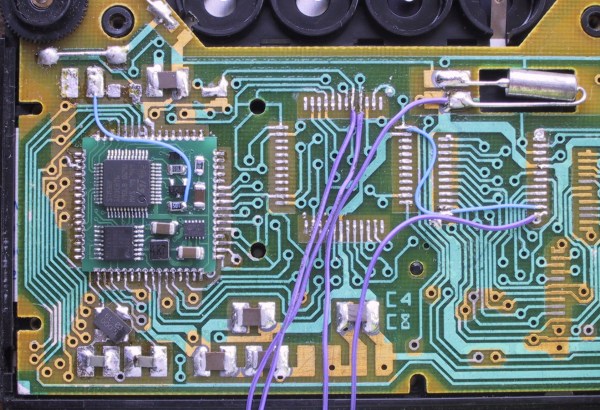

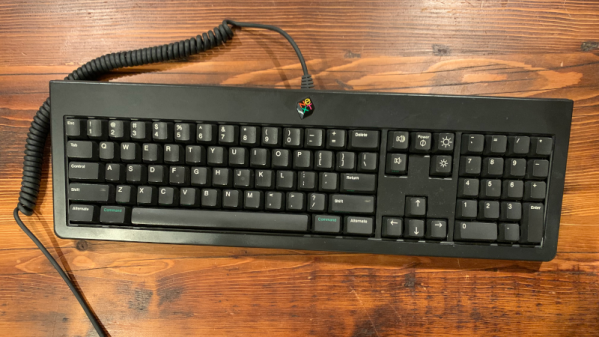

One of the brave but unsuccessful plays from Nokia during their glory years was the N-Gage, an attempt to merge a Symbian smartphone and a handheld game console. It may not have managed to dethrone the Game Boy Advance but it still has a band of enthusiasts, and among them is [Michael Fitzmayer] who has produced a CMake-based toolchain for the original Symbian SDK. This is intended to ease development on the devices by making them more accessible to the tools of the 2020s, and may serve to bring a new generation of applications to those old Nokias still lying forgotten in dusty drawers.

In much of the public imagination, the invention of the smartphone came with the release of the first Apple iPhone in 2007. Hackaday readers will of course trace the smartphone back much further than that to an original IBM prototype, and will remind any doubters that the Nokias which the iPhone vanquished were very successful smartphones without any of Cupertino’s magic in sight. Nokia’s tragedy was that they appeared not to understand what they had in Symbian, and released a bewildering array of devices intended to satisfy every possible market without recognizing that the market they needed to serve was their customers being easily able to run the apps of their choice on the things.

Symbian itself has long ago become a piece of abandonware, but during its chequered history there was a period in which an open-source version was released. It would be nice to think that projects such as this one might revive interest in this capable yet forgotten operating system, as with the passage of a decade the cost of hardware which might run it has fallen to the point of affordability. Does anyone want to relive the 2000s?

Header image: Evan-Amos, Public domain.