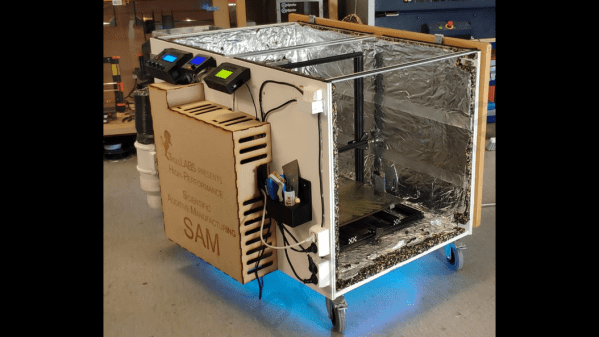

With the widespread adoption of emulators, almost anyone can start playing video games from bygone eras. Some systems are even capable of supporting homebrew games, with several having active communities that are still creating new games even decades later. This ease of programming for non-PC platforms wasn’t always so easy, though. If you wanted to develop games on a now-antique console when it was still relatively new, you had to jump through a lot of hoops. [Tore] shows us how it would have been done with his Sega Mega Drive development kit that he built from scratch.

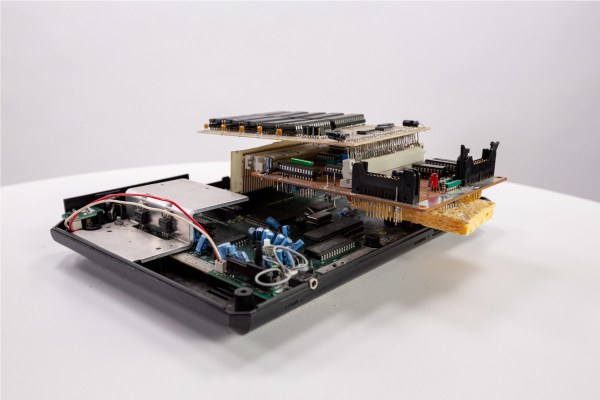

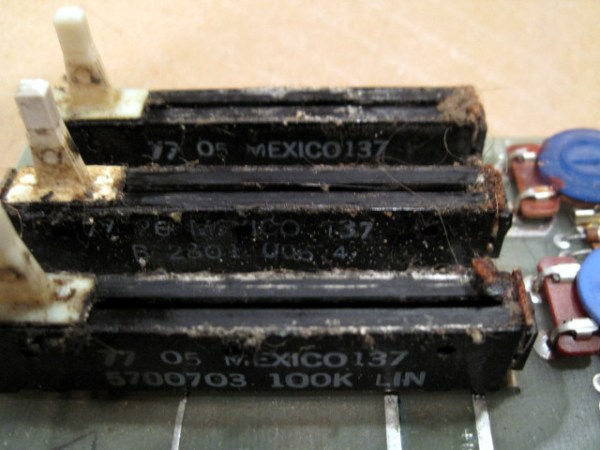

While [Tore] had an Atari ST, he wanted to do something a little more cutting edge and at the time there was nothing better than the Mega Drive (or the Genesis as it was known in North America). It had a number of features that lent the platform to development, namely the Motorola 68000 chip that was very common for the time and as a result had plenty of documentation available. He still needed to do quite a bit of reverse engineering of the system to get a proper dev board running, though, starting with figuring out how the cartridge system worked. He was able to build a memory bank that functioned as a re-writable game cartridge.

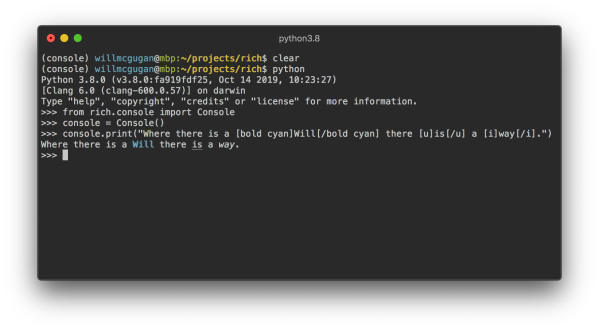

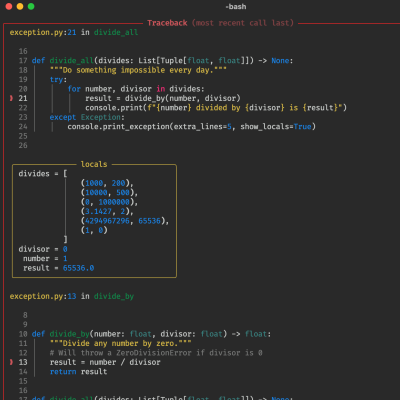

With the hard parts out of the way [Tore] set about building the glue logic, the startup firmware which interfaced with his Atari ST, and then of course wiring it all together. He was eventually able to get far enough along to send programs to the Mega Drive that would allow him to control sprites on a screen with the controller, but unfortunately he was interrupted before he could develop any complete games. The amount of research and work to get this far is incredible, though, and there may be some helpful nuggets for anyone in the homebrew Mega Drive community today. If you don’t want to get this deep into the Mega Drive hardware, though, you can build a cartridge that allows for development on native Sega hardware instead.