Many early home video game consoles were developed by American and Japanese companies: think Nintendo, Commodore, and Atari. But on the other side of the Iron Curtain, which was still very much in place in the 1980s, an entirely separate industry was built on names like Tesla and Elektronika. As a resident of the republic of Georgia, [Thomas] over at Workshop Nation has built up a sizeable collection of such Soviet-era hardware. A while back, he stumbled upon an Elektronika Video Sport 3, a 1990-vintage Pong-like video game console made in the USSR, and made a delightful video that shows him bringing it back to life.

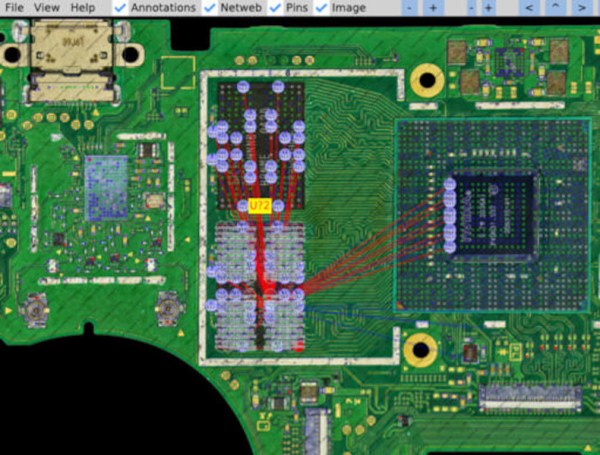

Like its Western counterparts, the Video Sport 3 is built around a dedicated chip, in this case a K145IK17. This is a Soviet clone of the GI AY-3-8500 that powered nearly every TV Pong console in the West, allowing it to run several variations of Pong as well as a simple target shooting game. Interestingly, the Video Sport 3 also has a “test” mode in which it outputs a test signal to help you adjust your TV settings — quite useful in the days of analog CRTs. It also came with a comprehensive user manual, as well as full schematics to help you repair it in case anything breaks.

Like its Western counterparts, the Video Sport 3 is built around a dedicated chip, in this case a K145IK17. This is a Soviet clone of the GI AY-3-8500 that powered nearly every TV Pong console in the West, allowing it to run several variations of Pong as well as a simple target shooting game. Interestingly, the Video Sport 3 also has a “test” mode in which it outputs a test signal to help you adjust your TV settings — quite useful in the days of analog CRTs. It also came with a comprehensive user manual, as well as full schematics to help you repair it in case anything breaks.

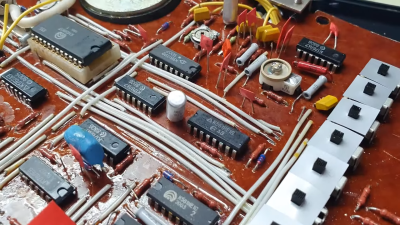

[Thomas]’s device didn’t immediately work, which is why he opened it up and tried to find any errors. The main board he found inside was a beautifully hand-made, single-layer board with around a dozen chips and lots of discrete components. Nothing seemed obviously broken, but [Thomas] decided to replace a few electrolytic capacitors as a precaution. This turned out to be enough to get the console working again — dodgy caps truly are a universal problem with older hardware.

A small Elektronika black-and-white TV that [Thomas] found earlier forms a perfect complement to the Video Sport 3. Together, they give us a glimpse into what a typical video game setup may have looked like in an early 1990s Soviet home. In fact, the Eastern Bloc supplied a reasonably wide selection of home computers, although not many people could actually buy them. Some truly bizarre machines were also produced for professional users.

Continue reading “Soviet-Era Pong Console Is Easy To Repair” →