Back in the day, an FM bug was a handy way to make someone’s annoying radio go away, particularly if it could be induced to feedback. But these days you’re far more likely to hear somebody’s Bluetooth device blasting than you are an unruly FM radio.

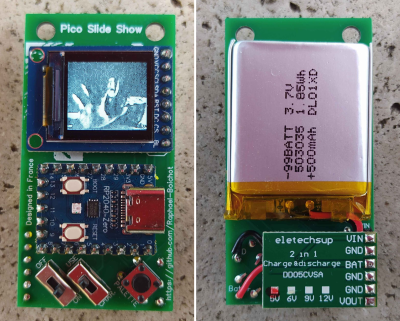

To combat this aural menace, [Tixlegeek] is here with a jammer for the 2.4 GHz spectrum to make annoying Bluetooth devices go silent. While it’s not entirely effective, it’s still of interest for its unashamed jankiness. Besides, you really shouldn’t be using one of these anyway, so it doesn’t really matter how well it works.

Raiding the AliExpress 2.4 GHz parts bin, there’s a set of NRF24L01+ modules that jump around all over the band, a couple of extremely sketchy-looking power amplifiers, and a pair of Yagi antennas. It’s not even remotely legal, and we particularly like the sentence “After running the numbers, I realized it would be cheaper and far more effective to just throw a rock at [the Bluetooth speaker]“. If there’s a lesson here, perhaps it is that effective jamming comes in disrupting the information flow rather than drowning it out.

This project may be illegal, but unlike some others we think it (probably) won’t kill you.