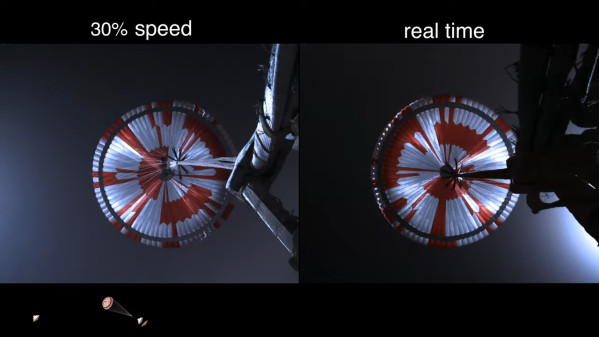

The much-anticipated video from the entry descent and landing (EDL) camera suite on the Perseverance rover has been downlinked to Earth, and it does not disappoint. Watch the video below and be amazed.

The video was played at the NASA press conference today, which is still ongoing as we write this. The brief video below has all the highlights, but the good stuff from an engineering perspective is in the full press conference. The level of detail captured by these cameras, and the bounty of engineering information revealed by these spectacular images, stands in somewhat stark contrast to the fact that they were included on the mission mainly as an afterthought. NASA isn’t often in the habit of adding “nice to have” features to a mission, what with the incredible cost-per-kilogram of delivering a package to Mars. But thankfully they did, using mainly off-the-shelf cameras.

The camera suite covered nearly everything that happened during the “Seven Minutes of Terror” EDL phase of the mission. An up-looking camera saw the sudden and violent deployment of the supersonic parachute — we’re told there’s an Easter egg encoded into the red-and-white gores of the parachute — while a down-looking camera on the rover watched the heat shield separate and fall away. Other cameras on the rover and the descent stage captured the skycrane maneuver in stunning detail, both looking up from the rover and down from the descent stage. We were surprised by the amount of dust kicked up by the descent engines, which fully obscured the images just at the moment of “tango delta” — touchdown of the rover on the surface. Our only complaint is not seeing the descent stage’s “controlled disassembly” 700 meters away from the landing, but one can’t have everything.

Honestly, these are images we could pore over for days. The level of detail is breathtaking, and the degree to which they make Mars a real place instead of an abstract concept can’t be overstated. Hats off to the EDL Imaging team for making all this possible.

Continue reading “Stunning Footage Of Perseverance Landing On Mars”