Whenever a project calls for displaying numbers, a 7-segment display is the classic and straightforward choice. However, if you’re more into a rustic, retro, almost mystical, and steampunky look and feel, it’s hard to beat the warm, orange glow of a Nixie tube. Once doomed as obsolete technology of yesteryear, they have since reclaimed their significance in the hobbyist space, and have become such a frequent and deliberate design choice, that it’s easy to forget that older devices actually used them out of necessity for lack of alternatives. Exhibit A: the impulse counter [soldeerridder] found in the attic that he turned into a general-purpose, I2C controlled display.

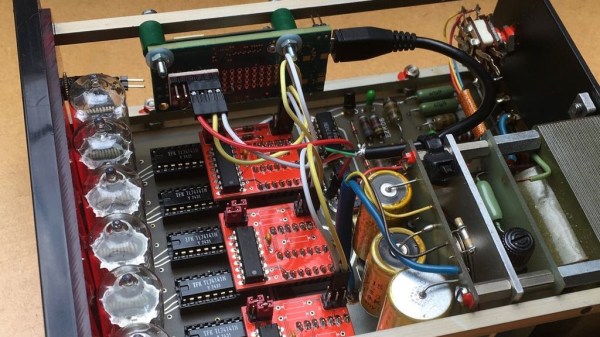

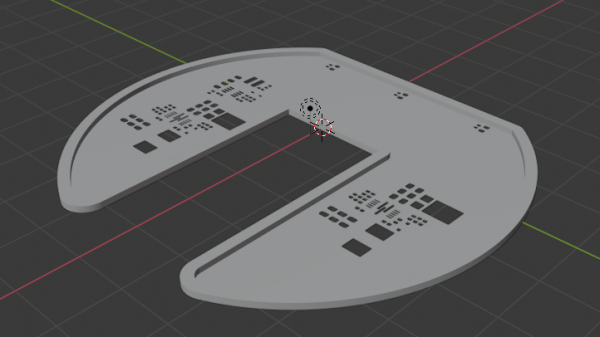

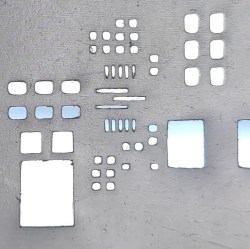

Instead of just salvaging the Nixie tubes, [soldeerridder] kept and re-used the original device, with the goal to embed an Intel Edison module and connect it via I2C. Naturally, as the counter is a standalone device containing mainly just a handful of SN74141 drivers and SN7490 BCD counters, there was no I2C connectivity available out of the box. At the same time, the Edison would anyway replace the 7490s functionality, so the solution is simple yet genius: remove the BCD counter ICs and design a custom PCB containing a PCF8574 GPIO expander as drop-in replacement for them, hence allowing to send arbitrary values to the driver ICs via I2C, while keeping everything else in its original shape.

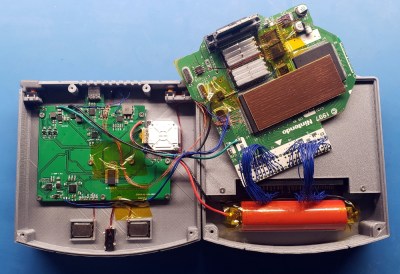

Containing six Nixie tubes, the obvious choice is of course to use it as a clock, but [soldeerridder] wanted more than that. Okay, it does display the time, along with the date, but also some sensor values and even the likes on his project blog. If you want to experiment with Nixie tubes yourself, but lack a matching device, Arduino has you obviously covered. Although, you might as well go the other direction then.

Continue reading “BCD To I2C: Turning A Nixie Counter Into Whatever You Want It To Be”