Even a relatively low-end desktop 3D printer will have no problems running off custom enclosures or parts for your latest project, and for many, that’s more than worth the cost of admission. But if you’re willing to put in the time and effort to become proficient with necessary CAD tools, even a basic 3D printer is capable of producing complex gadgets and mechanisms which would be extremely time consuming or difficult to produce with traditional manufacturing techniques.

Once you find yourself at this stage of your 3D printing career, there’s something of a fork in the road. The most common path is to design parts which are printed and then assembled with glue or standard fasteners. This is certainly the easiest way forward, and lets you use printed parts in a way that’s very familiar. It can also be advantageous if you’re looking to meld your own printed parts with existing hardware.

The other option is to fully embrace the unique capabilities of 3D printing. Forget about nuts and bolts, and instead design assemblies which snap-fit together. Start using more organic shapes and curves. Understand that objects are no longer limited to simple solids, and can have their own complex internal geometries. Does a hinge really need to be two separate pieces linked with a pin, or could you achieve the desired action by capturing one printed part inside of another?

If you’re willing to take this path less traveled, you may one day find yourself creating designs such as this fully 3D printed turntable by Brian Brocken. Intended for photographing or 3D scanning small objects without breaking the bank, the design doesn’t use ball bearings, screws, or even glue. Every single component is printed and fits together with either friction or integrated locking features. This is a functional device that can be printed and put to use anywhere, at any time. You could print one of these on the International Space Station and not have to wait on an order from McMaster-Carr to finish it.

With such a clever design, I couldn’t help but take a closer look at how it works, how it prints, and perhaps even some ways it could be adapted or refined going forward.

Continue reading “Printed It: Hand Cranked Photography Turntable”

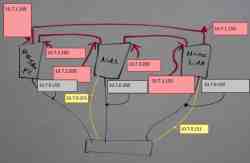

The drone hardware used by [Ogün Levent] and his team is a custom-made S600 frame with T-Motor U3 motors and a 40 A speed controller, with a takeoff weight of 5 kg. An

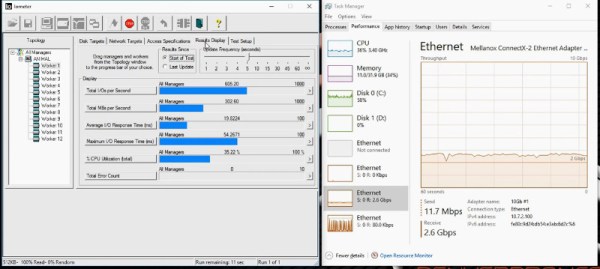

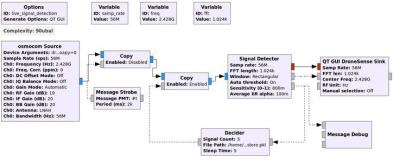

The drone hardware used by [Ogün Levent] and his team is a custom-made S600 frame with T-Motor U3 motors and a 40 A speed controller, with a takeoff weight of 5 kg. An  One of the LimeSDRs runs a GNU radio flowgraph with a specially designed block for detecting the rogue drone’s frequency modulation signature with what seems to be a machine learning classification script. The other LimeSDR runs another *secret* flowgraph and a custom script running on the SBC combines the two flowgraphs together.

One of the LimeSDRs runs a GNU radio flowgraph with a specially designed block for detecting the rogue drone’s frequency modulation signature with what seems to be a machine learning classification script. The other LimeSDR runs another *secret* flowgraph and a custom script running on the SBC combines the two flowgraphs together.