Many languages feature a random number generator library for help with tasks like rolling a die or flipping a coin. Why, you may ask, is this necessary when humans are perfectly capable of randomly coming up with values?

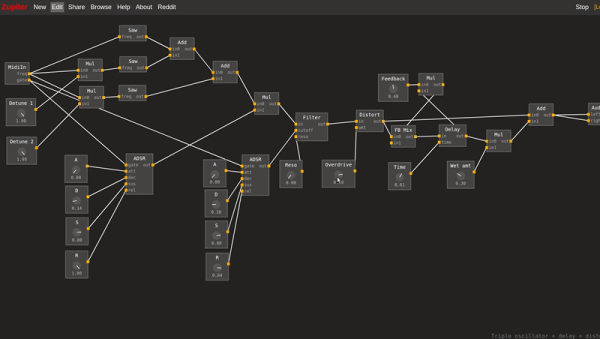

[ex-punctis] was curious about the same quandary and decided to code up an experiment to test the true randomness of human. A script guesses the user’s next input from two choices, keeping a tally in the JavaScript backend that holds on to the past five choices. If the script guesses correctly, they take $1 from the user. Otherwise, the user earns $1.05.

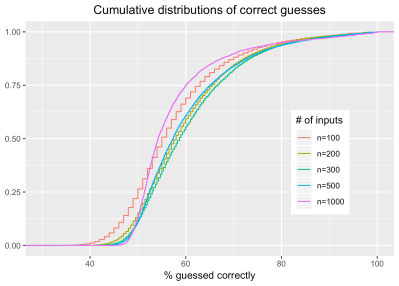

The data from gathered from running the script with 200 pseudo-random inputs 100,000 times resulted in a distribution of correct guess approximately normal (µ=50% and σ=3.5%). The probability of the script correctly guessing the user’s input is >57% from calculating µ+2σ. The result? Humans aren’t so good at being random after all.

It’s almost intuitive why this happens. Finger presses tend to repeat certain patterns. The script already has a database of all possible combinations of five presses, with a counter for each combination. Every time a key is pressed, the latest five presses is updated and the counter increases for whichever combination of five presses this falls under. Based on this data, the script is able to make a prediction about the user’s next press.

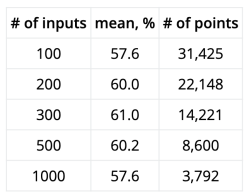

In a follow-up statistic analysis, [ex-punctis] notes that with more key presses, the accuracy of the script tended to increase, with the exception of 1000+ key presses. The latter was thought to be due to the use of a psuedo random number generator to achieve such high levels of engagement with the script.

Some additional tests were done to see if holding shorter or longer sequences in memory would account for more accurate predictions. While shorter sequences should theoretically work, the risk of players keeping a tally of their own presses made it more likely for the longer sequences to reduce bias.

There’s a lot of literature on behavioral models and framing effects for similar games if you’re interested in implementing your own experiments and tricking your friends into giving you some cash.