[Mike Harrison] produces so much quality content that sometimes excellent material slips through the editorial cracks. This time we noticed that one such lost gem was [Mike]’s reverse engineering of the 6th generation iPod Nano display from 2013, as caught when the also prolific [Greg Davill] used one on a recent board. Despite the march of progress in mobile device displays, small screens which are easy to connect to hobbyist style devices are still typically fairly low quality. It’s easy to find fancier displays as salvage but interfacing with them electrically can be brutal, never mind the reverse engineering required to figure out what signal goes where. Suffice to say you probably won’t find a manufacturer data sheet, and it won’t conveniently speak SPI or I2C.

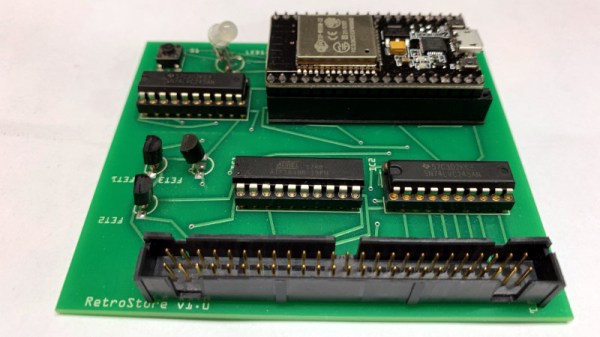

After a few generations of strange form factor exploration Apple has all but abandoned the stand-alone portable media player market; witness the sole surviving member of that once mighty species, the woefully outdated iPod Touch. Luckily thanks to vibrant sales, replacement parts for the little square sixth generation Nano are still inexpensive and easily available. If only there was a convenient interface this would be a great source of comparatively very high quality displays. Enter [Mike].

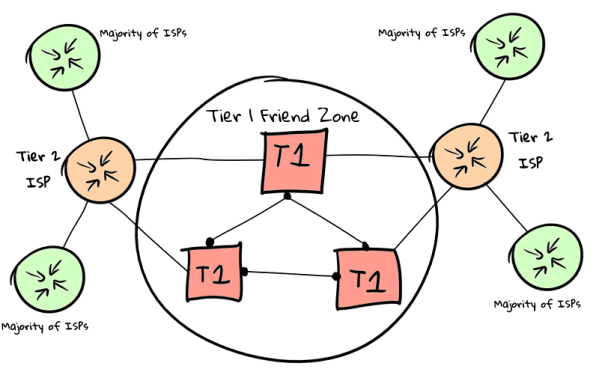

This particular display speaks a protocol called DSI over a low voltage differential MIPI interface, which is a common combination which is still used to drive big, rich, modern displays. The specifications are somewhat available…if you’re an employee of a company who is a member of the working group that standardizes them — there are membership discounts for companies with yearly revenue below $250 million, and dues are thousands of dollars a quarter.

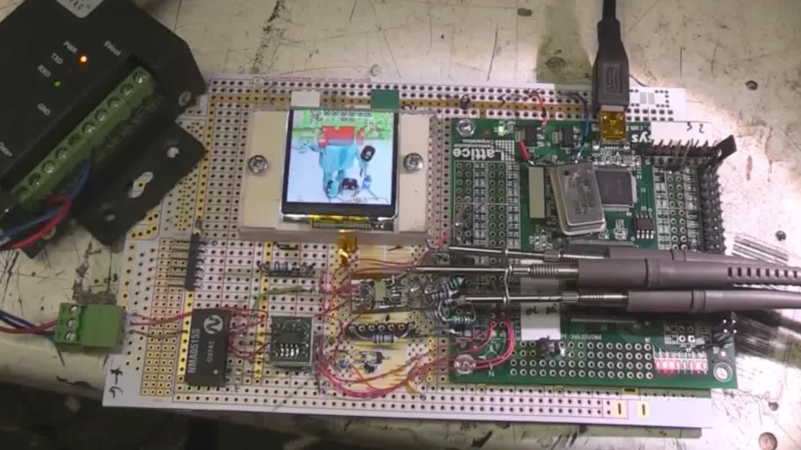

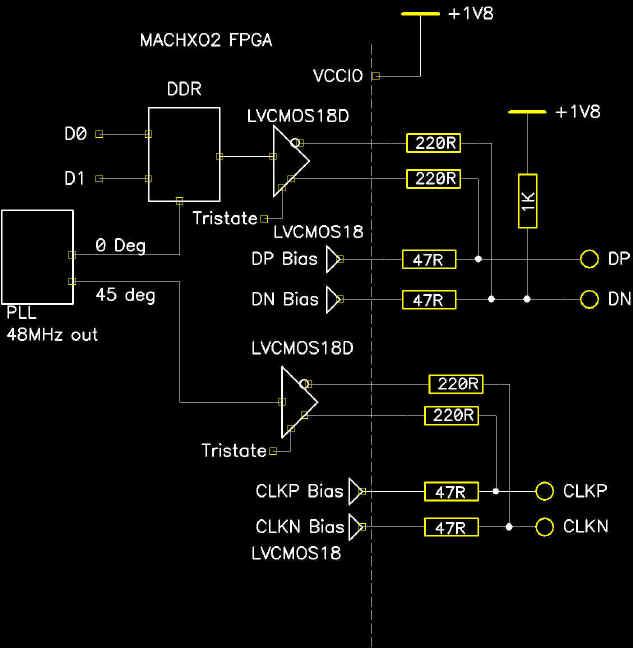

Fortunately for us, after some experiments [Mike] figured out enough of the command set and signaling to generate easily reproduced schematics and references for the data packets, checksums, etc. The project page has a smattering of information, but the circuit includes some unusual provisions to adjust signal levels and other goodies so try watching the videos for a great explanation of what’s going on and why. At the time [Mike] was using an FPGA to drive the display and that’s certainly only gotten cheaper and easier, but we suspect that his suggestion about using a fast micro and clever tricks would work well too.

It turns out we made incidental mention of this display when covering [Mike]’s tiny thermal imager but it hasn’t turned up much since them. As always, thanks for the accidental tip [Greg]! We’re waiting to see the final result of your experiments with this.