Right now, we’re running the Repairs You Can Print Contest, where one lucky student and one lucky organization will win the fancy-schmancy Prusa i3 MK3, with the neato multi-extrusion upgrade. [Budiul] is a student, so he figured he would repair something with a 3D printer. Lucky for him, the pegboard in his workshop was completely terrible, or at least the pegboard hooks were. These hooks were made out of PVC, and after time, more and more hooks broke. The solution? Print his own, and make them stronger in the process.

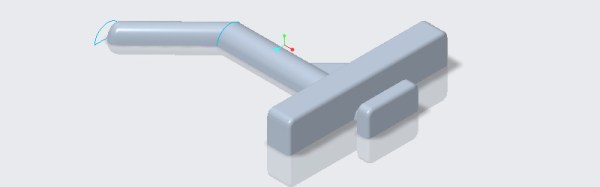

[Budiul] started his fix by taking the remaining, unbroken hooks on his pegboard wall organizer and measuring the relevant dimensions. These were modeled in Creo 4.0, printed out, and tested to fit. After many errors and failed models, he finally got a 3D printable version of his plastic pegboard hooks.

Of course, replacing PVC pegboard hooks with ABS hooks really isn’t that great of a solution. To fix this problem of plastic pegboard hooks for good, he printed the hooks in halves, with a channel running down the middle. This channel was filled with some steel wire and acetone welded together. The result is a fantastically strong pegboard hook that will hold up to the rigors of holding up some tools.

While printing out pegboard hooks might not seem like the greatest use of time, there are a few things going for this hack. Firstly, these aren’t the pegboard hooks made out of steel rod we all know and love; this is some sort of weird proprietary system that uses plastic molded hooks. If they’re made out of plastic anyway, you might as well print them. Secondly, being able to print your own pegboard hooks is a severely underrated capability. If you’ve ever tried to organize a workbench, you’ll know that you’ll never be able to find the right hook for the right spot. There is, apparently, a mystical superposition of pegboard hooks somewhere in the universe.

This is a great hack, and a great entry for the Repairs You Can Print contest. You can check out a video of the hack below.

Continue reading “Repairs You Can Print: Fixing Pegboard Clips That Break Too Easily”