Ask any security professional and they’ll tell you, when an attacker has hardware access it’s game over. You would think this easily applies to arcade games too — the very nature of placing the hardware in the wild means you’ve let all your secrets out. Capcom is the exception to this scenario. They developed their arcade boards to die with their secrets through a “suicide” system. All these decades later we’re beginning to get a clear look at the custom silicon that went into Capcom’s coin-op security.

Alas, this is a “part 1” article and like petulant children, we want all of our presents right now! But have patience, [Eduardo Cruz] over at ArcadeHacker is the storyteller you want to listen to on this topic. He is part of the team that figured out how to “de-suicide” the CP2 protections on old arcade games. We learned of that process last September when the guide was put out. [Eduardo] is now going through all the amazing things they learned while figuring out that process.

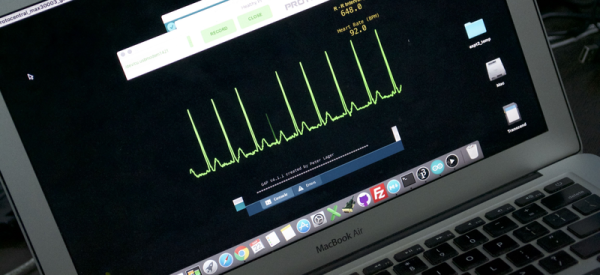

These machines — which had numerous titles like Super Street Fighter II and Marvel vs. Capcom — used battery-backed ram to store an encryption key. If someone tampered with the system the key would be lost and the code stored within undecipherable thanks to “two four-round Feistel ciphers with a 64-bit key”. The other scenario is that battery’s shelf life simply expires and the code is also lost. This was the real motivation behind the desuicide project.

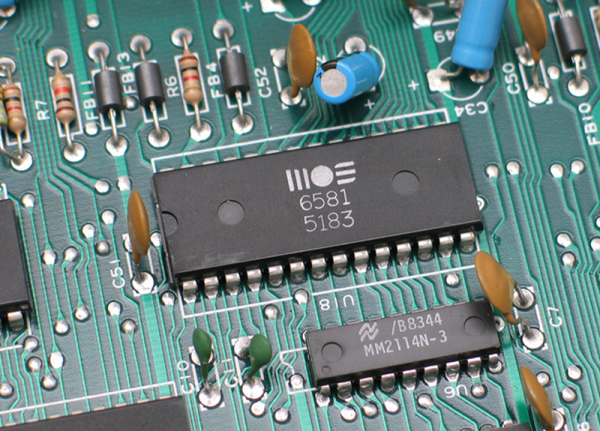

An overview of the hardware shows that Capcom employed at least 11 types of custom silicon. As the board revisions became more eloquent, the number of chips dropped, but they continued to employ the trick of supplying each with battery power, hiding the actual location of the encryption key, and even the 68000 processor core itself. There is a 6-pin header that also suicides the boards; this has been a head-scratcher for those doing the reverse engineering. We assume it’s for an optional case-switch, a digital way to ensure you void the warranty for looking under the hood.

Thanks for walking us through this hardware [Eduardo], we can’t wait for the next installment in the series!