For many of us, it’s difficult to imagine a world without Maker Faire. The flagship events in California and New York have served as a celebration of the creative spirit for a decade, giving hackers and makers a rare chance to show off their creations to a live audience numbering into the hundreds of thousands. It’s hard to overstate the energy and excitement of these events; for anyone who had the opportunity to attend one in person, it’s an experience not soon forgotten.

Unfortunately, a future without Maker Faire seemed a very real possibility just a few months ago. In May we first heard the events were struggling financially, and by June, we were saddened to learn that organizer Maker Media would officially be halting operations. It wasn’t immediately clear what would happen to the flagship Maker Faires, and when Maker Media reluctantly admitted that production of the New York Faire was officially “paused”, it seemed we finally had our answer.

But as the recent Philadelphia Maker Faire proved, the maker movement won’t give up without a fight. While technically an independent “Mini” Faire, it exemplifies everything that made the flagship events so special and attracted an impressive number of visitors. With the New York event left in limbo, the Philadelphia Faire is now arguably the largest event of its type on the East Coast, and has the potential for explosive growth over the next few years. There’s now a viable option for makers of the Northeast who might have thought their days of exhibiting at a proper Maker Faire were over.

But as the recent Philadelphia Maker Faire proved, the maker movement won’t give up without a fight. While technically an independent “Mini” Faire, it exemplifies everything that made the flagship events so special and attracted an impressive number of visitors. With the New York event left in limbo, the Philadelphia Faire is now arguably the largest event of its type on the East Coast, and has the potential for explosive growth over the next few years. There’s now a viable option for makers of the Northeast who might have thought their days of exhibiting at a proper Maker Faire were over.

We’ll be bringing you detailed coverage of some of the incredible projects that were on display at the Philadelphia Maker Faire over the coming days, but in the meantime, let’s take a quick look at some of the highlights from this very promising event.

Continue reading “Maker Spirit Alive And Well At The Philly Maker Faire”

![Czech waste management workers dismantle scrap washing machines. Tormale [CC BY-SA 3.0].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1280px-DVO_4792.jpg?w=400)

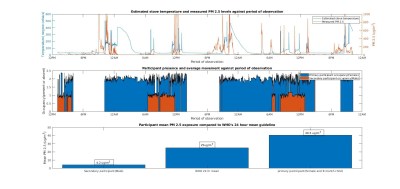

Within the second household, a typical energy mix of charcoal briquettes and kerosene was typically used for cooking, with kerosene used during the day and briquettes used at night. The results from measuring pollution levels using OpenHAP showed that the mother and child in the household regularly received around 1.5 x the recommended limit of pollutants, enough to lead to slow suffocation.

Within the second household, a typical energy mix of charcoal briquettes and kerosene was typically used for cooking, with kerosene used during the day and briquettes used at night. The results from measuring pollution levels using OpenHAP showed that the mother and child in the household regularly received around 1.5 x the recommended limit of pollutants, enough to lead to slow suffocation.